“Two months ago I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a son. When something happened to Negroes in the South, I said, “that’s their business not mine”. Now I know how wrong I was. The murder of my son has shown me that what happens to any of us, anywhere in the world, had better be the business of us all.” Mamie Till

It was Saturday mid-morning in Sumner, Tallahatchie County Mississippi when we pulled up in front of the courthouse. For a moment I wondered whether we had driven onto a Hollywood movie set. Not a soul was in the street. I half-expected tumbleweed to blow down the street. It was unnerving. On one side of the courthouse a sign informed us that we were at the place where, in a five-day murder trial held in the courthouse in 1955, two white men were acquitted of the murder of 14-year old Emmett Till. Incongruously, on the opposite side of the courthouse, stands a statue erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy* to honour their heroes.

As we waited for our guide we wandered around the street, peeking through the windows of closed shops, wondering why no one was out shopping, banking, doing Saturday morning kind of things. That eerie feeling followed me into the courthouse as we took our seats, the majority of our group on the left of the courtroom where the all-white, all-male jury would have sat, to listen to our guide, Ben Saulsberry.

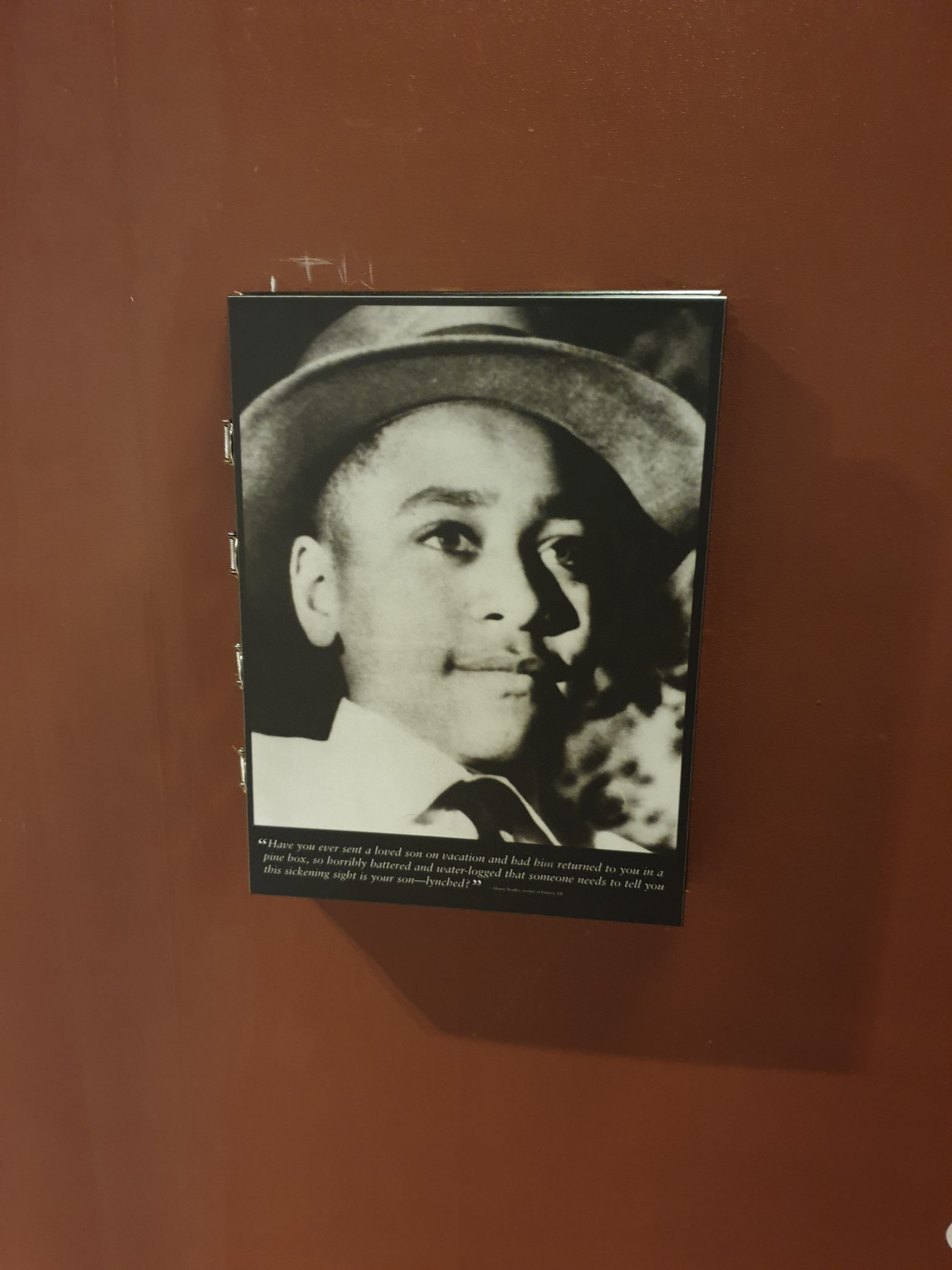

Till was a fourteen-year-old boy from Chicago who, in the summer of 1955, begged his mother to allow him to travel with his cousin to visit relatives in Mississippi. Mamie Till let her son go with misgivings, worried that he wouldn’t know the ways of the South (i.e. how a black person should behave). She didn’t know that the next time she saw him it would be as a barely recognisable corpse in a wooden box. He had been abducted, beaten, shot in the head, tied with barbed wire to a large metal fan and his body dumped in the Tallahatchie River. His crime – whistling at a young white woman.

In spite of overwhelming evidence, and positive identification by Till’s uncle, the jury acquitted Till’s killers, Bryant and Milam. A few months later they would sell their story to a magazine, confessing to the crime, knowing that they could not be retried for a crime they had already been acquitted of.

What ultimately took Emmett’s life was racism, Saulsberry told us. His message was one of hope, saying that the pain needed to be processed through telling the truth to enable us to move forward. In 2007 the courthouse was restored and is now preserved as a memorial, a community centre and a space to share Till’s story as a way of working towards “racial reconciliation”. Progress is slow but Saulsberry optimistically points out that 20 years ago there was no conversation at all. However, he cautioned that we are not off the hook for doing the work to create a new narrative.

In a powerful exercise, Saulsberry invited us to read a resolution that had been presented to Till’s family in 2007, outside the courthouse. The resolution starts,

We the citizens of Tallahatchie County believe that racial reconciliation begins with telling the truth. We call on the state of Mississippi, all of its citizens in every county, to begin an honest investigation into our history.

Each one of us read a sentence in turn, going around the room until we had come to the last sentence, which we read as a group,

Working together we have the power now to fulfil the promise of “liberty and justice for all”

Striking a chord deep inside me were my two sentences,

While it will be painful, it is necessary to nurture reconciliation and to ensure justice for all.

We need to understand the system that encouraged these events and others like them to occur so that we can ensure that it never happens again.

Later in the trip, I would see photographs of the funeral, a mother bent over double with grief at the graveside of her only child. Her pain from losing her son so violently, is palpable. I wondered if she had blamed herself for not being firmer about preventing him from going South, to a place she knew was not like Chicago. Till’s mother bravely insisted that her son not only be buried in Chicago but that the casket should be open so that “the world could see what had been done to her baby”. Tens of thousands of people viewed his badly beaten body at the funeral, photographs were taken and published in the media … creating awareness and perhaps, ensuring that her son’s death was not in vain, his funeral a protest demonstration of its own.

His murder and the ensuing trial would lead to civil rights activist, Rosa Parks, refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a segregated bus. I thought about Emmett Till and I could not go to the back, she said. Ultimately it would set in motion the Montgomery bus boycotts, laying the foundation of the civil rights movement of the 60s. It was during the Montgomery boycott that a young Martin Luther King Jnr would emerge as a leader.

Many times on our “freedom riders” trip I was confronted by this story, at museums in Jackson, Montgomery and Washington DC (where his casket is on display), and I wanted to believe so fervently that his death and the deaths and suffering of many others, in his country and mine, were not in vain. Many times I wept as I witnessed the cruelty and hatred borne out of racism and traced the path of a past that won’t go away. Many times I wondered how we are meant to move forward to reconciliation when we don’t learn from the past. Perhaps this bearing witness, confronting our history and talking about the pain, is a way that I can contribute.

“This is precisely when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language that. That is how civilisations heal.” Toni Morrison

Read more https://www.emmett-till.org/

The featured image is of a photograph of Emmett Till in the Lowndes County Interpretive Center in the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail.

*The organisation was started by Southern women to commemorate their men who died in a war that was primarily fought to protect their right to own slaves.