I drive past the wasteland of what used to be District Six, on a regular basis, the few houses, places of worship and the CPUT buildings emphasise the starkness, highlighting what is no longer there. But recently, that emptiness struck me anew. Perhaps it was the viewpoint I had from the school which I had attended so many years ago. As I stood in the car park in front of the chapel on the Zonnebloem Estate, looking down the hill towards the ocean, I was overcome by a sense of loss. Through the gap above the wall where there used to be a gate, was only open field. I remembered the rows of houses that had stood there, the women who had made toffee apples, koeksisters and tameletjies, and the children who ran to buy these offerings through the fence, at break time.

Walking around the school gave me a curious sense of déja vu, of having lived in this space which is not quite the same. The buildings stand where they have stood for decades, but are rundown and in desperate need of TLC, the cobbled stones in the avenue we walked up to the chapel, have been covered by tar, and the school seemed smaller than I remembered. Memories came creeping back like the cobbles emerging from under the tar in places, refusing to be forgotten. Assemblies on the tarmac, Wednesday morning chapel, going home with smudges of ash on our foreheads on Ash Wednesday, uniform inspections and sitting at our desks eating our lunch before we could go out to play, because “young ladies did not eat outside”, and walking to the new Art Centre, where Mr Hopley taught.

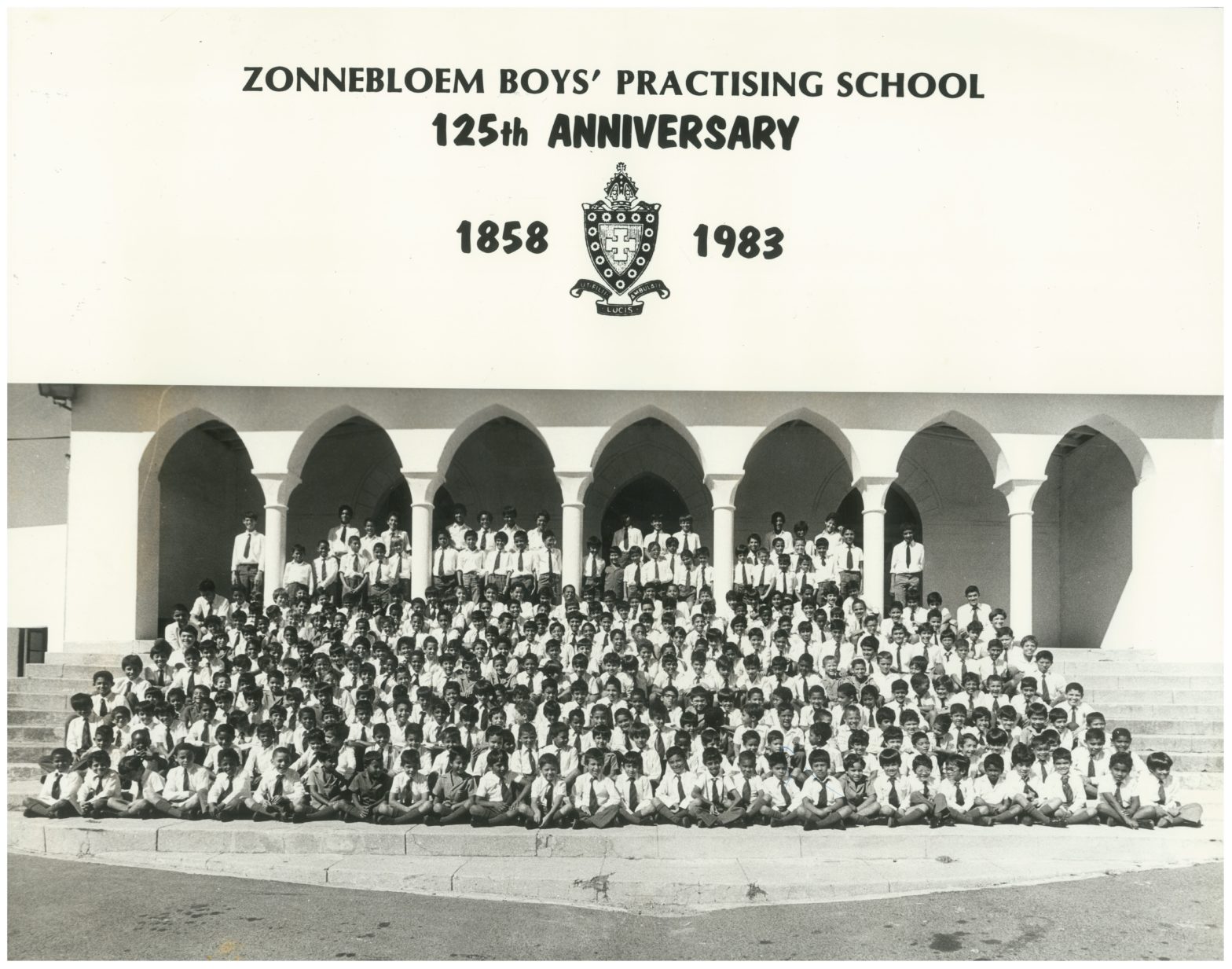

I think of Zonnebloem as the “family school” – an aunt taught at the boys’ school, my brothers and cousins attended the school and various family members, my father included, had trained at the teachers’ college which is now the high school. Zonnebloem was started in 1858 by Bishop Gray who had started Bishops and St Cyprian’s, both for ‘white’ children, while Zonnebloem initially targeted the sons of African chiefs, “to remove them from heathen and barbarous influences and expose them to the full force of civilisation”. Later girls were brought to the Cape to study so that the boys would have Christian wives rather than “heathen girls”. In the early 1920s, the school concentrated on the training of ‘coloured’ teachers, to promote decency and respectability as the path to civilisation.

Zonnebloem was one of the good ‘coloured’ schools, relatively speaking. When I recently interviewed a past-teacher, she recalled with fondness the ethos of the school, the dedication of her colleagues. She said that the teachers did the best they could to instil pride and a positive sense of belonging. With dedicated teachers, limited resources but a determination to educate children who the apartheid government deemed lesser than, Zonnebloem produced fine graduates, who returned to teach or to give back to the community in other ways. One of these alumni was Jeremiah Moshoeshoe, the son of King Moshoeshoe, who studied there in 1859 and showed such promise that he was sent to study further at St Augustine Missionary College in Canterbury. Another was Harold Cressy who came to Zonnebloem in 1897 from Natal when he was 8 years old. He graduated in 1905 as a teacher at the age of 16 years and completed matric through studying on his own. Rejected by Rhodes University because of the colour of his skin, he was eventually accepted by the University of Cape Town where he became the first ‘coloured’ person to attain a bachelor’s degree. Cressy left a significant mark on education, so much so that the Harold Cressy High School was named after him in 1953.

Bishops and St Cyprian’s continue to flourish as among the top private (mainly white) schools in the province and country, while Zonnebloem’s buildings and facilities slowly but steadily decline … an indictment perhaps, on our post-apartheid society in which little has changed economically, and the most vulnerable continue to suffer. Ironically, Zonnebloem, because of its prime location, has been designated a quintile 5 school, which serves the wealthiest communities and therefore receives the least government funding. It is a state school on private property in buildings leased from the Anglican church. The pupils, however, are from the most socio-economically vulnerable communities and are largely Xhosa-speaking. Children come on buses and taxis rather than walking like I did with my two brothers.

I had not been back to the school since I left in the mi-1970s but was invited to the Sunflower festival, held at the school earlier this year, by Zephne Ladbrook of the Otto Foundation. Ladbrook and her foundation have over the last two years injected pockets of hope into these potentially dreary surroundings – opening a library that doubles up as an aftercare space, renovating two classrooms and erecting a pre-fab building for two more, engaging in various other projects to improve the experience of learners at the school. She dreams of sports fields which would serve not only the schools on the Zonnebloem Estate, but those in the surrounding area, none of which have access to sport facilities. The school is adjacent to land which would be ideal for this purpose but for a number of bureaucratic reasons, is unavailable for development as such.

I find it inconceivable that we still have to motivate for sports to be part of an inclusive programme to develop children and youth. Apart from the obvious health and fitness benefits, participation in sport has been proven to enhance academic and psychosocial development. Children learn so much more than how to play the game when they participate in sport – perseverance, patience, teamwork and building self-esteem are just some of the skills that enhance development into healthy, well-rounded and mature adults. Sport can also play a major role in reducing criminal activity and substance abuse. I would argue that sport should be on an equal footing with language, maths and science, in developing our children.

Above all that, participating in sport provides opportunity to integrate within, and with other, communities, and here is where I see the overwhelming benefits of promoting sport at Zonnebloem that includes the surrounding schools. Ladbrook has swept me up in her vision of communities coming together to play on the Zonnebloem fields. District Six has become symbolic of the forced removals and destruction of communities that occurred during apartheid. How wonderfully appropriate then it would be if the estate were to become a hub of integration in the area, at once addressing the wrongs of the past, celebrating the legacy of the Zonnebloem alumni and shaping a generation of well-rounded individuals for a democratic South Africa. Perhaps this integration and redress will even include St Cyprian’s in the City Bowl and Bishops in the southern suburbs, drawing increasingly larger circles of inclusion and hope.

Potential projects which the Otto Foundation are hoping to complete are:

- A new cricket field in partnership with WP Cricket.

- A feeding scheme/vegetable garden in partnership with Ladles of Love and Rise Against Hunger.

- Fix up bathrooms spaces and provide ‘dignity packs’ for girls in order to restore dignity.

- Water storage and maintenance in partnership with SOS NGO; and an upgrade of security

- Expansion of cultural extramurals such as a choir

The Otto Foundation would value support from local businesses and alumni and may be contacted via the following emails: zephne@chrisottofoundation.com or karen@chrisottofoundation.com

This article was published in The Cape Argus 25 October 2018.