When I turned 50, I decided that it was time to equip myself with the tools necessary to write the stories of where we come from. I was convinced that providing a platform to share and acknowledge our painful past was fundamental to reconciliation in our country. Certainly, after 25 years of democracy we seemed to be no nearer to recognising each other as simply human. Being the mother of two young adults bestowed on me a sense of urgency. However, gaining a Masters in Creative Writing (from the same university that in the 1980s required me to apply for a government permit to attend because of the colour of my skin), opened up the path to a deeply personal journey, one that would lead to a PhD in History and Heritage Studies.

Early on in this journey it became clear that I needed to retrace our history way back to the arrival of the Dutch at the Cape, an event that occurred within the global context of slavery and colonialism in which they were major players. The impact of slavery and colonisation on South African society has receded far behind the more dominant history of apartheid and yet, the racial hierarchy that accompanied it not only laid the foundation for apartheid, but shaped attitudes to race and sex that continue to inform the present.

The benign version of slavery presented to us at school was reinforced by charming paintings of colonial Cape Town, the colourful houses of the Bo-Kaap and images of benevolent masters who wanted only to ‘civilise’ and take care of the black bodies under their care. This narrative concealed the brutality and dehumanisation of the people who were brought here as a source of labour, a commodity, to be sold and traded. After emancipation, other ways to maintain control over workers were introduced, such as the notorious dop system that has left its legacy of foetal alcohol syndrome and high infant mortality rates in the Western Cape.

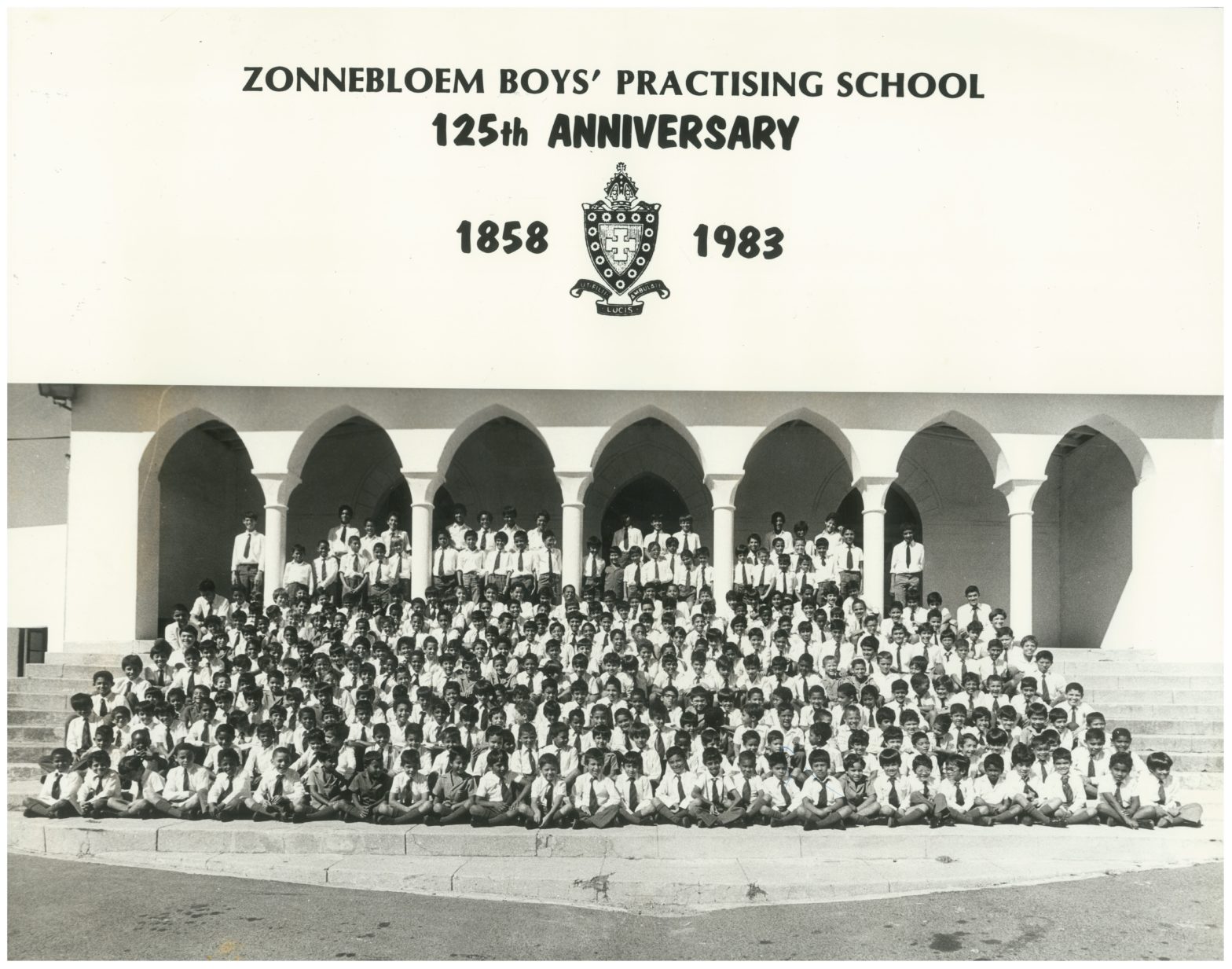

Racial slavery was about the degradation of the human being and simply being emancipated was not enough to know what it meant to be free, how to recreate ourselves and become independent. Apartheid tried to force us into being the same – we lived in the same areas, went to the same schools, married the same people. We carried our sameness around like a security blanket and retreated within it, afraid of the other; we developed our own stereotypes based on our ignorance of what was beyond those walls. More than simply the dismantling of apartheid legislation needs to be done in order that we may construct ways of life in which we acknowledge our human-ness rather than other-ness.

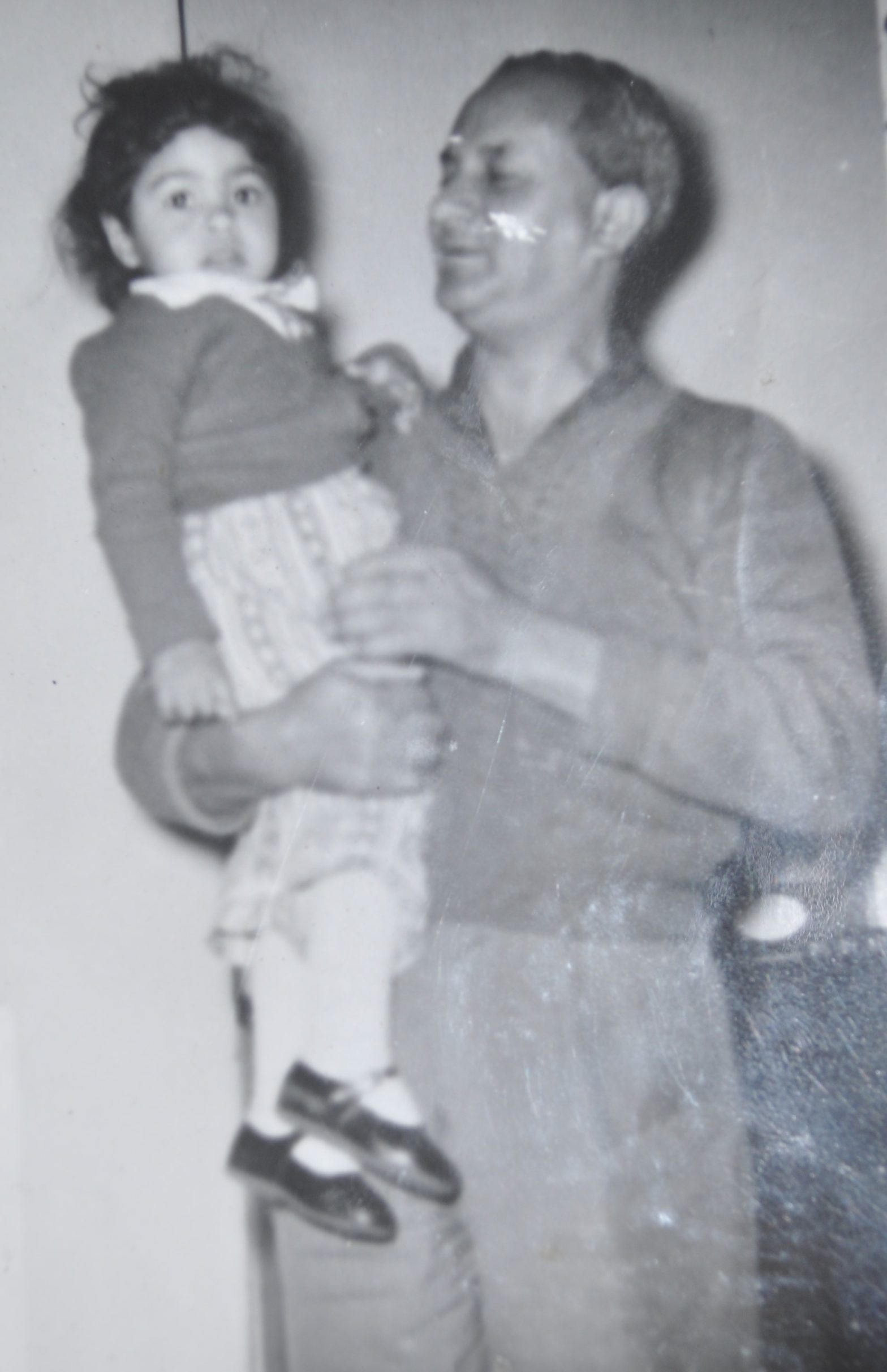

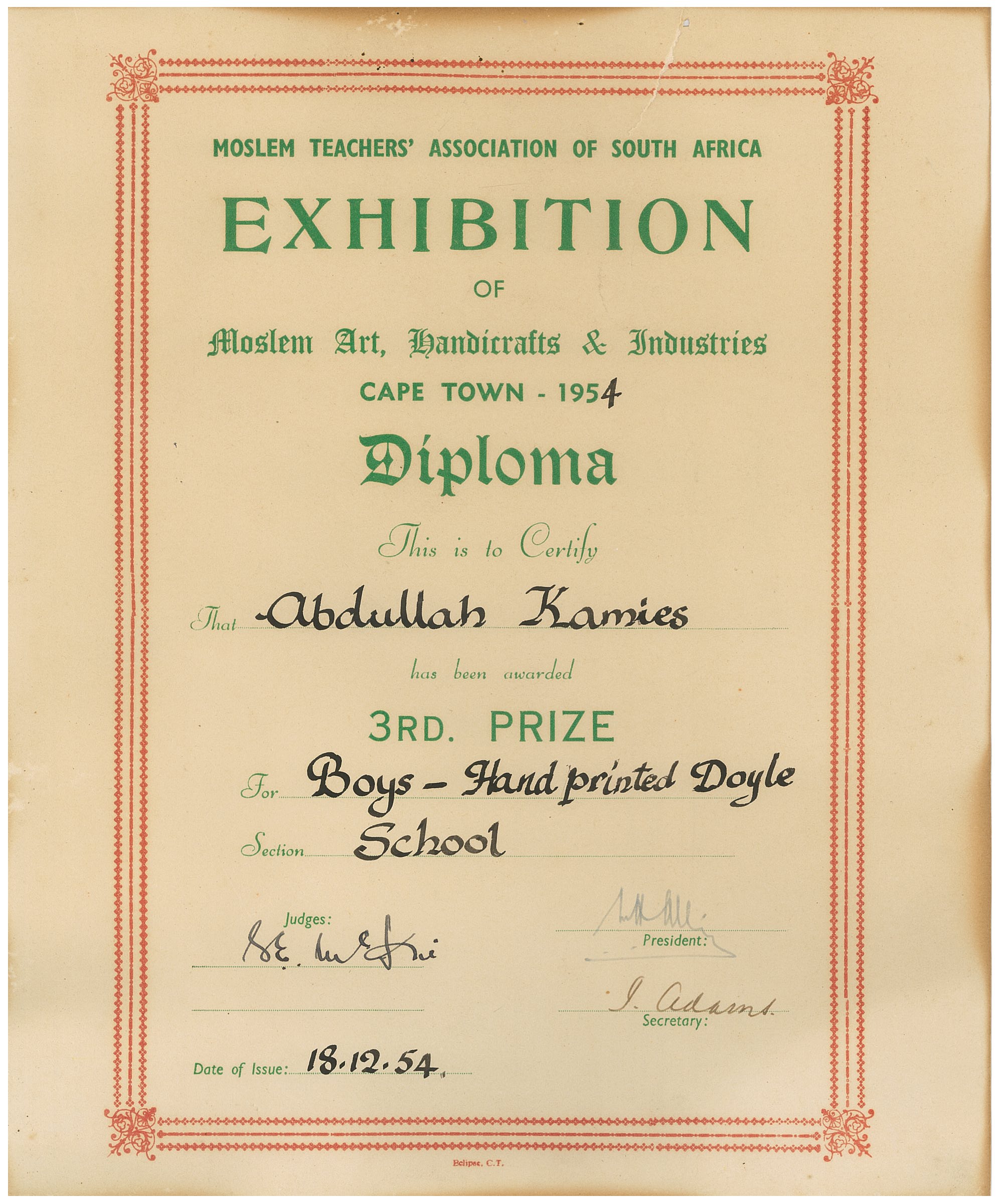

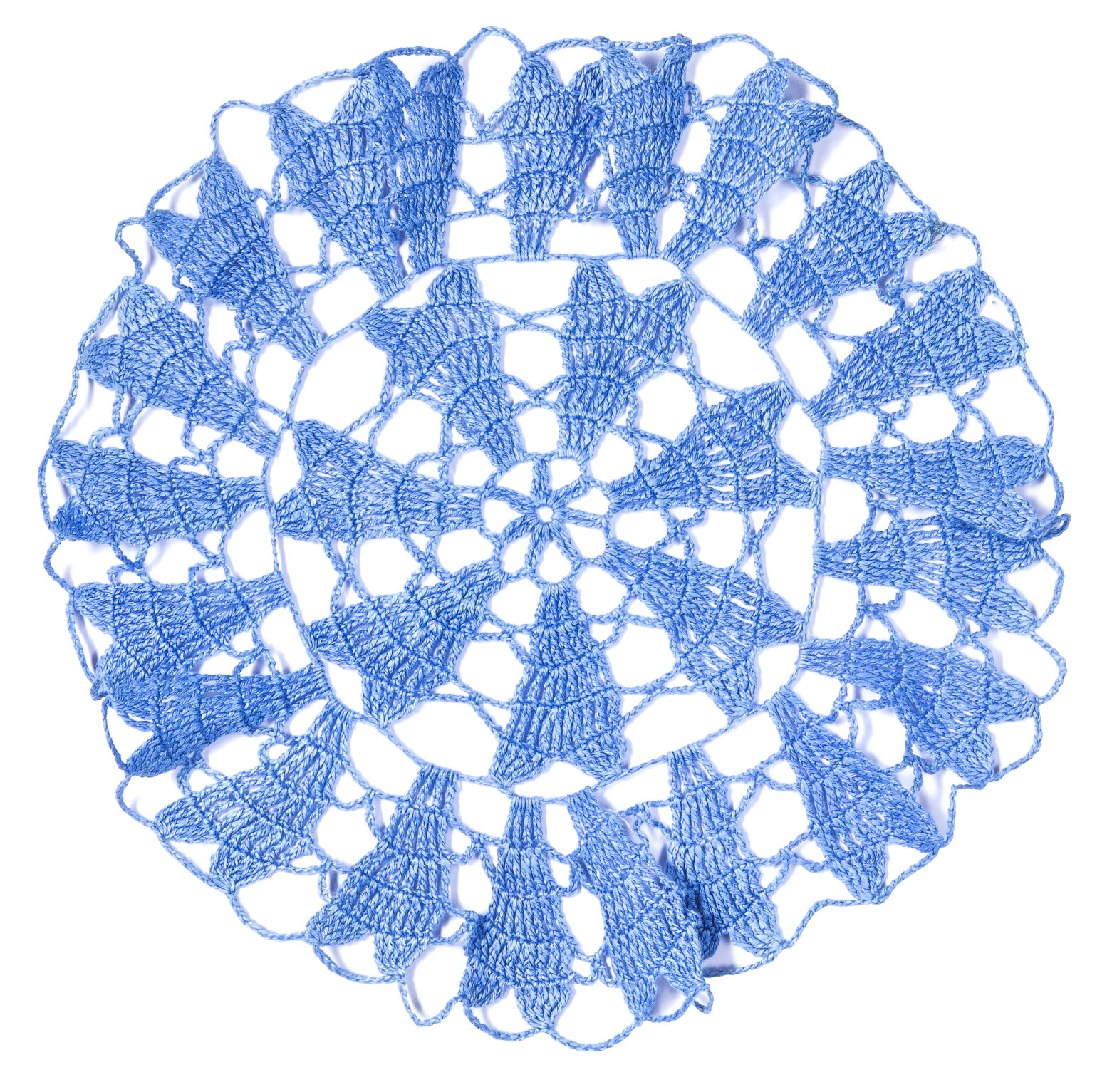

But, to remember slavery is also to remember the vibrant and diverse cultures, new language, food, music and beliefs that arose, and to honour the spirit of survival and resistance that was engendered. Somehow people managed to find ways to survive and hold onto that which made them human. These practices of freedom – music, art and storytelling – defy and resist the memories of slavery and apartheid and attest to a will to survive. Even the humble family photograph, in spite of it often showing little skill, and found stuffed into boxes or envelopes, has the power to destabilise the dominant narrative that would have us believe that we were less-than. They speak to the resistance of the human to being objectified and it is at this ordinary archive that we need to look if we want to understand what it means to be human.

By connecting the lines between all of our stories, whether they are auditory, visual or written, we may recognise our common humanity; we break down the walls that were constructed around us, to separate us from the other. When we reach out to each other we move beyond the process of othering, and towards freedom and equality so that we may think about how we may live. Only then may we learn how to be human.

Images from my family album.

This piece prefaces the virtual exhibition, KWAAI Vol. 3 by Cape Town gallery, eclectica contemporary.

Read a review of the exhibition here.