Katrina was on her knees scrubbing the kitchen floor when she felt the faintest kick, almost like a flutter in her belly. She sat back on her heels and cupped her wet hands over the spot. There it was again, like butterflies in her stomach…like the butterflies in Namaqualand…in spring…when the flowers were out. That’s the one time of the year a person could say the place was beautiful. After the rains they’d be rewarded with carpets of yellow or purple, for all the months of emptiness. A person could almost ignore the holes gouged out of the earth by men digging for diamonds or copper, as the broken landscape burst into life. She smiled at the memory of running barefoot through fields of flowers, making a daisy chain to crown her baby sister and holding her breath as a butterfly balanced on her shoulder.

Ag, there she went again, wasting time on daydreams, her madam would say. She shook her head as if to get rid of the images and sighed as she picked up the scrubbing brush again. She’d left the vygies and daisies, the aloes and the orchids, behind a long time ago. She couldn’t remember when last she’d spoken to her brothers and sisters. If it wasn’t for the black and white photograph stuck into the mirror in her room, she wondered if she would even remember what they looked like. Bitterfontein. The name said it all, she thought to herself as she got up with another sigh. The bitterness had even seeped into the water. At least here she had a job; there was one less mouth for her father to feed. It didn’t help to worry about things a person could do nothing about.

“Katrina, I’m leaving now,” Mrs Laing shouted down the passage. “Don’t forget to bring in the washing before you go off. It looks like rain. And make sure the gate is locked properly this time.”

“Yes, Madam,” Katrina replied, poking her head round the kitchen door. “See you tomorrow, Madam.”

Katrina had been working for Mrs. Laing, a white lady, in Roeland Street for a year now. Her madam worked her hard but she was grateful to have a job where she could live in. It also paid better than her previous job and she was off on Saturday afternoons. “But no men and no drink allowed,” Mrs. Laing had warned when she started.

Katrina finished up, washed and changed into a pink floral dress, gathered under the bodice with a generous skirt which skimmed over her hips and stomach. She wanted to go see Hajji quickly this afternoon and maybe there would still be time to watch the new James Dean film playing at the Gem. She walked down Drury Lane towards District Six, to Combrinck Street where the dressmaker lived. The rows of semi-detached houses looked a little shabby but most people had made an effort with their front stoeps – they were painted red or green and polished every week, there was a potted delicious monster plant or two, and perhaps a bench to sit on in the evenings when the day’s work was done and a person had a chance to catch up with a neighbour.

Katrina went around the back of the house through the open kitchen door. There was no one there, but smells of onions braising with cardamom and cloves greeted her. She noticed the chopped cabbage, potatoes and mutton knuckles waiting to be added to the pot. Hajji must be making a bredie. She could hear the sound of the sewing machine coming from the back and called out, “It’s me, Katrina,” as she went in. Hajji was sitting behind the Singer which stood in the corner of her sons’ bedroom. Her head, covered with a scarf, was bowed in concentration as she guided the fabric through the threader and pumped the pedal of the black enamel machine. Four identical dresses in powder-blue satin hung on the front of the wardrobe. As a dressmaker Hajji’s beadwork was very popular with Malay and Christian brides, even the Jewish people came to her. The small room did double duty as her workroom by day. Her sons often complained that they had to watch out for pins in the bedspread or that they stepped onto beads on the floor with their bare feet. Hajji, practical as always, had told them to put on shoes and given them a magnet to pick up the pins.

Hajji had four children, and one from her husband’s first marriage, who was working at a butcher in Salt River. All three boys would soon leave school, one by one, to learn a trade. Hajji’s daughter, Fatima, was already apprenticed to a dressmaker in Walmer Estate.

“Salaam Hajji,” Katrina greeted, respectful of Hajji’s religion, even though she herself was Christian. “I see supper is cooking already. Hajji must be going out this evening.”

“Alaykum Salaam, Katrina,” said Hajji, taking the pins out of her mouth. “Yes, I’m very busy. I have to finish this dress tonight. That Van der Ross girl is getting married tomorrow. She lost weight again. I have to take the dress in. Poor child is already so thin.”

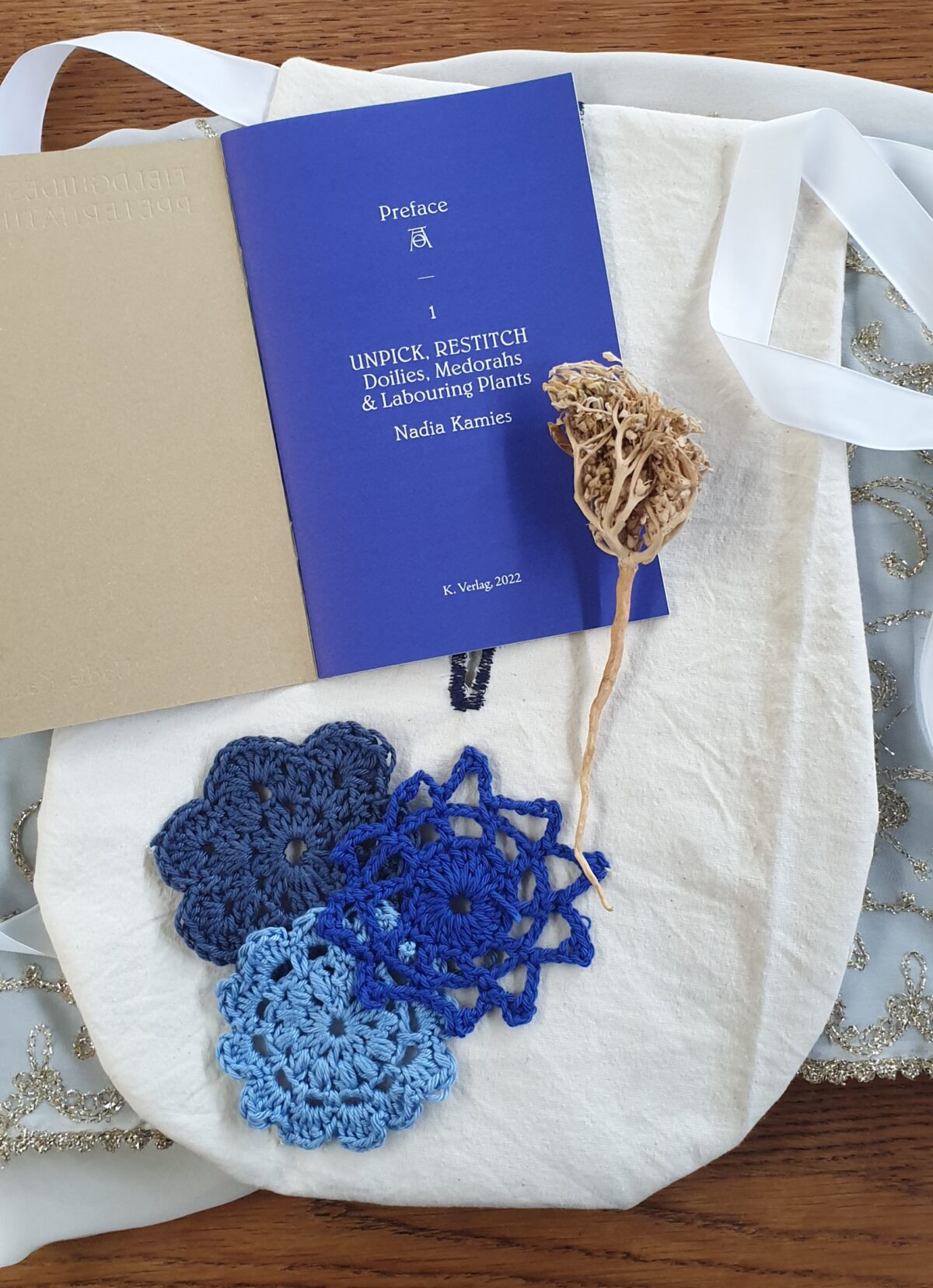

Hajji always did the final fitting the day before the wedding. She said it was bad luck to finish the dress too long before the time. So she made sure to put in the last stitches late at night, her fingers flying over the silk and satin. She delivered the beaded creation herself on the morning of the wedding. Hajji also dressed the bride in petticoats, underskirts of stiff netting, and finally the gown. She was skilled at shaping the gilded medora into a headdress. Sometimes she would be asked to prepare the bruidskamer for the Muslim brides as well, making drapes, cushions and quilted bedspreads with satin and lace.

When Hajji wasn’t busy with a wedding she made outfits for Eid or other special occasions and simple frocks with fabric she bought on the Grand Parade. Katrina and her friends bought these dresses on lay-bye, paying off a small amount every month. Hajji recognized the dress Katrina was wearing today as one she’d made last year.

“Can I make Hajji some tea?”

“Ag, Katrina, I don’t have time for tea now. Is there something you wanted?”

“Ja, Hajji, I have to talk to you about a problem. Hajji can mos see what’s going on with me.”

Katrina turned to the side in front of the mirror, and, placing one hand under her breasts, she smoothed the dress over her stomach with the other. There was no mistaking the curve of her belly when you looked at her profile. Her breasts were also fuller and Hajji realized she was glowing. She recalled that Katrina had mentioned the last dress she made for her was too tight but she hadn’t brought it to be altered yet.

“Ag man, Katrina, you’re pregnant aren’t you? I warned you.” Hajji clicked her tongue. “It’s that Ginger, isn’t it? And where’s he now? You let a white man take advantage of you. I told you, they don’t marry you. The man can pull up his pants and walk away. And then you sit with the problem.”

“Hajji, please don’t be cross with me,” Katrina said sitting down on the edge of one of the beds. “I’m so scared my madam is going to send me away when she finds out that I’m pregnant. What am I going to do? I can’t go home. My Pa will beat me. What about my Ma? She’ll be so ashamed that her daughter is pregnant. What will the people say at church? In any case, what will we live on? There’s no job, not enough food. I think Pa was only too happy when I said I was coming to Cape Town. How can I go home with another mouth to feed?”

“I suppose Mrs. Laing hasn’t noticed what you are hiding behind that big overall and apron she makes you wear. Mind you, it won’t be too long before she does. What if she throws you out? Then what are you going to do? Ooh, Katrina, where are you going to find another good job like this one?”

Hajji had a soft spot for Katrina. Before Hajji and her husband had gone to Mecca the year before, Katrina had come to help with all the visitors even though it was her afternoon off. She’d set the table with plates of biscuits and tarts (all made by Hajji), bowls of dried fruit and nuts bought from Wellington Fruit Growers in Darling Street, and Hajji’s best tea set with the gold teaspoons. Katrina was honest and worked hard, she deserved a chance. She was just attracted to the wrong men, always thinking this would be the one to take her away from it all.

Hajji had known that this Ginger would be trouble. From what she heard from Amiena, whose husband had the corner café, he was charming but unreliable. He didn’t seem to have a fixed job but always had money. Katrina was flattered that he took an interest in her, loved the status of having a white boyfriend. The other girls looked up to her when they saw the two of them together at the bioscope on a Saturday afternoon. They thought she was one of the lucky ones, maybe she could even “pass”, or maybe she and Ginger could go to Botswana or Swaziland to get married.

“Katrina, look, I don’t mind,” Hajji said, “I can look after the baby for a bit, to help you out. But only for a little bit, ok? Maybe your madam needs time to get used to the idea and then she’ll let you keep the baby there. Your madam thinks we’re stupid but everybody knows her daughter’s baby came six months after the wedding. She must think we don’t know how long a baby takes. Premature, my foot.”

Hajji had been sewing for Mrs. Laing for years; that’s how she and Katrina had met. She’d made the wedding dress for Mrs. Laing’s daughter, Sarah, and had pleated the layers of chiffon to drape over the beginnings of a bump, although no one had said a word.

An extract from a story published in The New Contrast 178 Vol 45 Winter 2017