Poet, book illustrator and artist, Peter Clarke, described his work as a reflection on humanity, on a commonality that surpasses all boundaries. Clarke, who died in 2014, was a former resident of Simon’s Town. His family was forcibly removed to the ‘coloured’ township of Ocean View due to the passing of the Group Areas Act, which assigned people to different residential areas based on their ‘race’.

Having spent some time looking at museums and working on proposals and exhibitions over the last year and a half, perhaps my expectations have dropped. Many of the little dorpies I have visited, have inadequate records of the history and events that affected the majority of their residents and little acknowledgement of the catastrophic apartheid-era events that forever changed the social and cultural landscape of their communities. Thus, I was gratified to see the efforts of the local historical/heritage society and the residents of Simon’s Town on a recent visit.

Apart from the “Wall of Memory”, a display project begun in 2014 by residents past and present, and organisations, there are markers that acknowledge various places of historical interest, such as Hospital Lane (that ran along the Royal Naval Hospital built in 1813) and Drostdy Steps (where the mayor (or landdrost), Christian Michiel Lind, lived in 1828).

Elsewhere, plaques record the place where a stream ran, from which the crewmen of ships filled their freshwater casks, and a building erected in 1772 by the Dutch East India Company for the governor’s visits to Simon’s Town. But the most poignant marker, for me, is the one dedicated

To the memory of generations of our fellow citizens

who dwelt here in peace and harmony

until removed by edict of 1967.

Erected by their fellow citizens

In the many conversations and interviews I have had over the last few years while doing my doctorate, I have been struck by two responses. Firstly, the lack of bitterness or need for revenge – yes, sometimes anger and often heartache, and secondly, a deep appreciation of the opportunity to be heard, to be given the platform to recount their experience and of having their suffering acknowledged. Often, people were disparaging about the value of their stories, almost brushing aside their experience with the observations that their suffering was not as bad as that of others. But always, there was a pride that their story mattered enough for me to write it down, that it could be included in my thesis, or in the exhibition at the museum.

The success of colonial expansion, slavery and later apartheid, lay in the ability of the oppressors to objectify those they wished to subjugate, to portray them as less than human. Clarke’s efforts to reflect the daily lives of people, their emotions and activities, speaks to a resistance of this objectification. He reflects their humanity. In the same way, the markers in the streets of Simon’s Town and exhibitions in its museum give a human face to the people who suffered under apartheid.

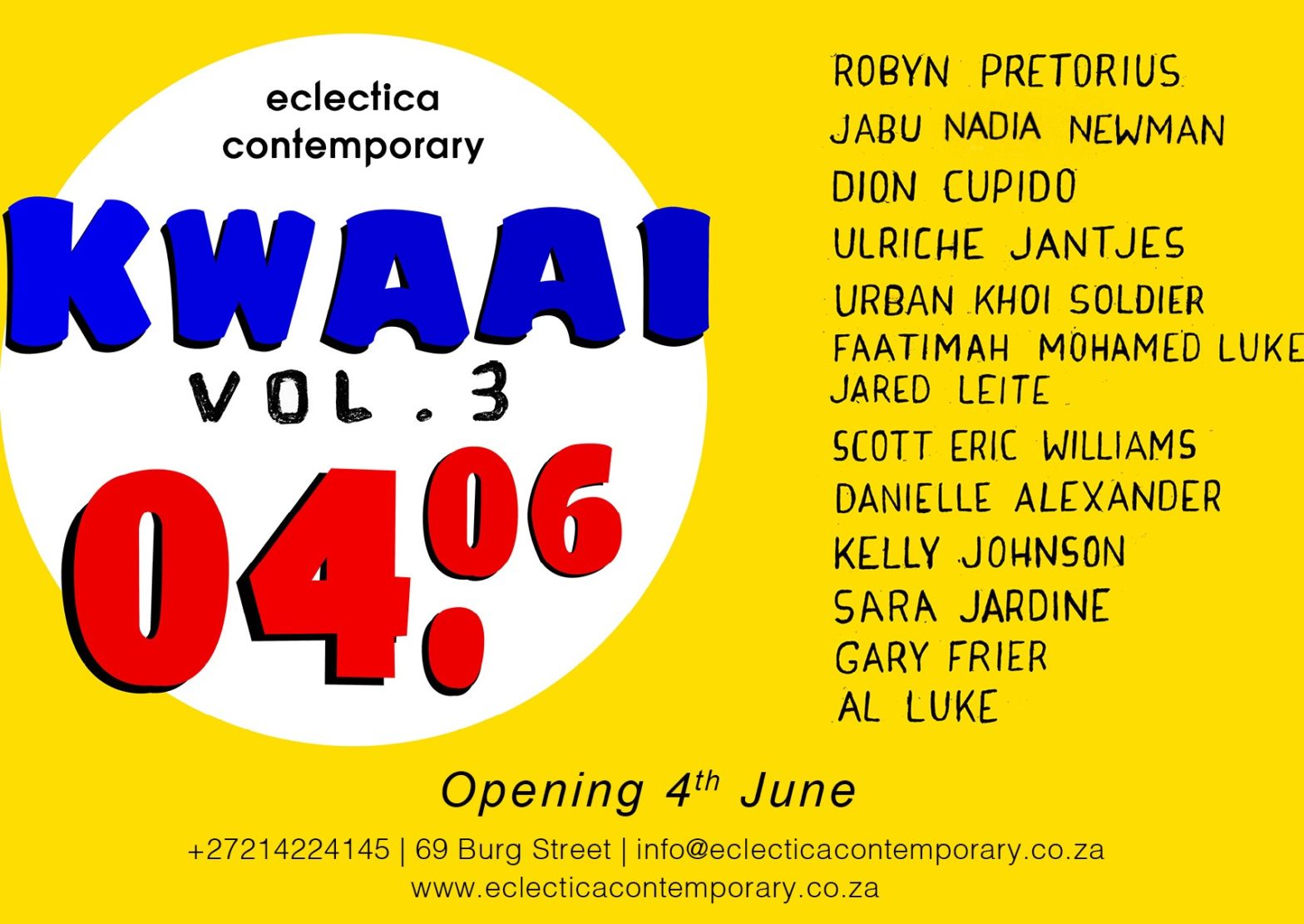

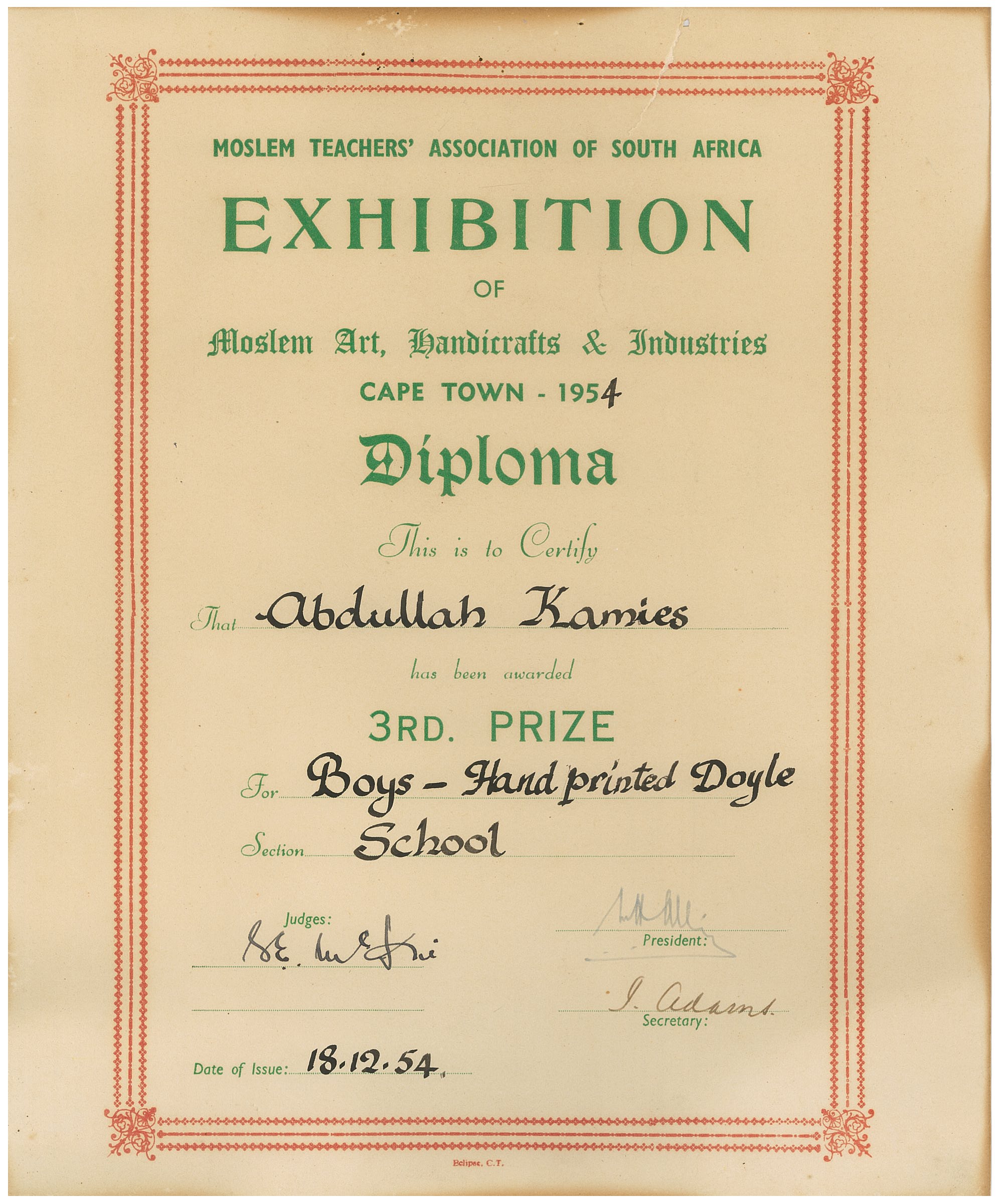

Ironically, under apartheid, the arts – music, dance, painting, story-telling and so on – the very practices of what makes us human, flourished. Many artists were forced to give up on their dreams or forced into exile in order to pursue them. Many ordinary people who may have gone on to greater achievements if not for the colour of their skin, the texture of their hair or the shapes of their noses… Former Simon’s Town residents like:

Dr Peter Clarke (2 June 1929 – 13 April 2014): Poet, book illustrator and visual artist whose work was showcased at exhibitions in England, Germany and the USA in the 1960s and who was invited to study printmaking in Holland and then etching in Norway.

Vincent Hantam: ballet dancer and teacher was principal dancer with the Scottish Ballet from 1975-1991. In September 2012, he became the first Artist-in-Residence at the University of Edinburgh.

Christoper Kindo (12 September 1955 – April 2015): ballet dancer, teacher and choreographer who studied at UCT Ballet School and was the only ‘coloured’ person in his class; in spite of being awarded best dancer in his class he was not hired by CAPAB after completing his training. He started Jazzart when he returned from a stint with the Boston Ballet company in the 1980s, before he became the first ‘coloured’ person to be principal dancer with CAPAB and ended his career at Dance for All.

Gladys Thomas (1944 -): poet, short-story writer, playwright and author of several children’s stories. Her debut anthology, Cry Rage, co-authored with another anti-apartheid South African poet, James Matthews, was published in 1971. This publication holds the distinction of being the first book of poetry to be banned in South Africa.

Our lives have meaning when we have been seen, listened to and acknowledged as human beings. I am reminded of the traditional Indian greeting, Namasté, a salutation of respect, acknowledging our essence of oneness. We are more the same than we are different. Namasté.

Footnote: On 22 September 2016 the Frank Joubert Art Centre where Clarke served as Artist-in-Residence, was renamed the Peter Clarke Art Centre. The following quote is from their website:

“My art is about people and the presence of people. The humanistic image is what interests me. I enjoy reflecting on people and their activities, their emotions, what could be events in their daily lives. But beyond that I speak via my symbols of activities on a larger, wider scale that transcends all boundaries…. I speak about a heritage of a common humanity.” – Peter Clarke, 1983

In the featured picture, two elderly men walk along the Wall of Memory in Main Road, Simon’s Town.