By: Prof Siona O’Connell, Critical African Studies Project, UP

Dr Nadia Kamies, Post-Doc Dept Historical & Heritage Studies, UP

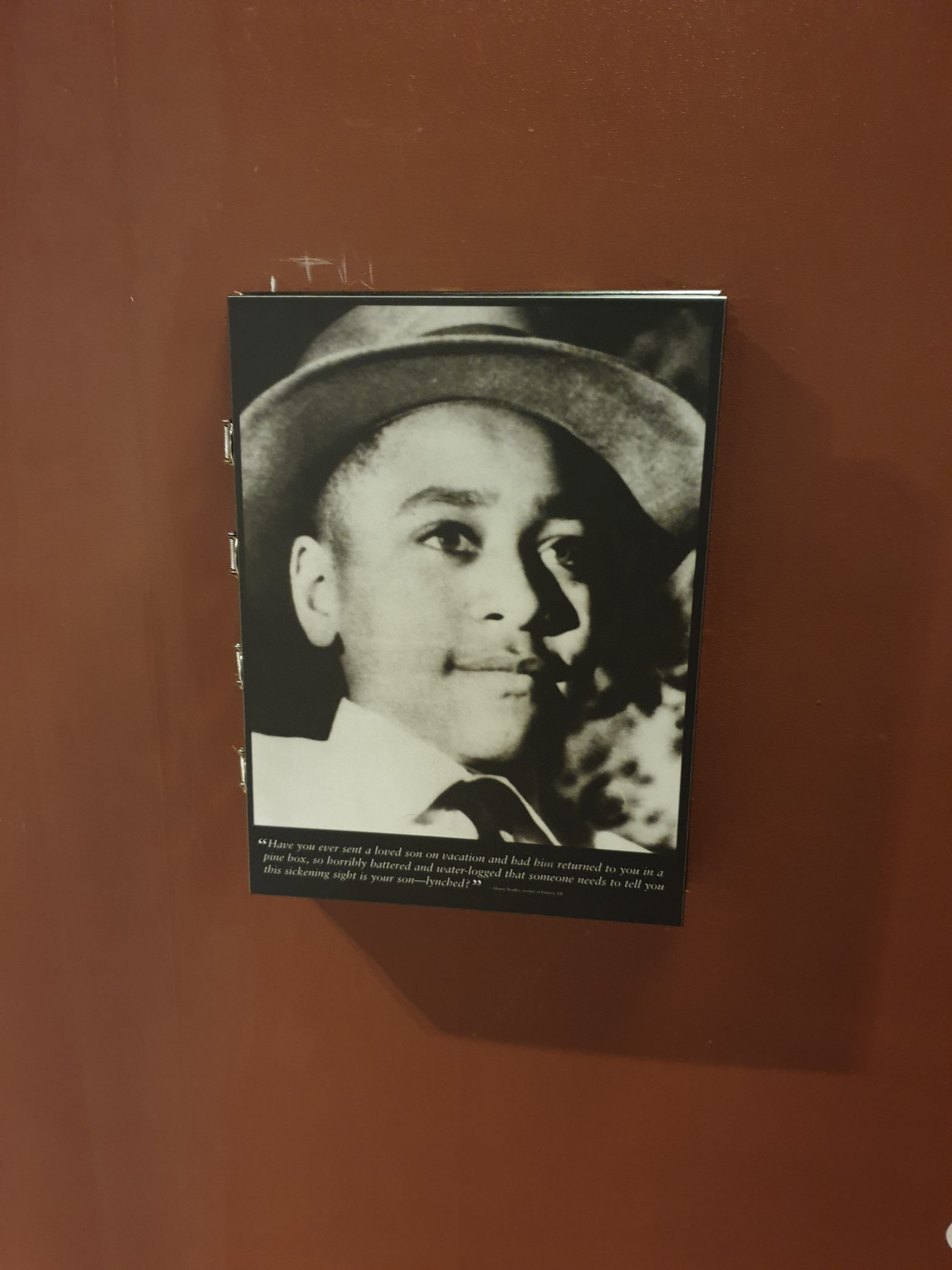

The forced removal of over 12 million Africans to the Americas was one part of the trade-in human bodies. Another aspect, is the people who were shipped to the Cape in the Indian Ocean slave trade. From its inception, the Cape was a slave society, violently established on the backs of men and women who were stripped of their names, cultures and religions, and forced to work in the kitchens and vineyards of their enslavers. In 1652, as colonial administrator of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), Jan Van Riebeeck dropped anchor at the Cape to establish a refreshment station with 100 men and eight women. A year later, the first known slave, Abraham van Batavia, a stowaway on board the Malacca, arrived.

The Dutch were active participants in both the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades. For brief spells during the 17th century they dominated the Atlantic slave trade and were at the centre of the most expansive slave trade in the history of Southeast Asia. The VOC, formed in 1602, was a sovereign body which acted independently of the Dutch government although its headquarters were in the Netherlands. They were granted a monopoly over trade in the East Indies, where they enslaved over half of the population of Batavia (now Jakarta) and protected their monopoly with brute force, while painting slavery as a “work of compassion”. Racial slavery was an economic, legal, political and cultural exercise based on the refusal to see ‘blacks’ as human and amply justified by the Bible.

In late August of 1791, the uprising in Santo Domingo (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) played a crucial role in the abolition of slavery, the slave trade and the weakening of colonialism. The British declared the slave trade illegal in 1807 and abolished the practice in all their colonies in 1834. Slaves at the Cape, however, were forced to serve an “apprenticeship” until 1838. On their emancipation, they had nowhere to go and had few possessions, if any. This created a dependency that served to tie many of the previously enslaved to their masters and the refuge the mission stations offered is thought to have ensured a close and steady supply of compliable workers to the surrounding farms. The Masters and Servants Ordinance of 1841 outlined how to accommodate ex-slaves and former “free blacks”, allowing employers to use certain disciplinary measures to control their behaviour. In fact, many of the Apartheid laws introduced in 1948 such as the pass laws and Group Areas Act reflected the restrictions used to control the movement of the enslaved.

Slavery was a central element of the Dutch colonial conquest and part of the emergence of Afrikaner political and social ideas. There can be no question that slavery fundamentally shaped South Africa from its earliest days and continued to do so along the continuum of colonialism and apartheid. As author and academic, Gabeba Baderoon (2014) observes “slavery generated foundational notions of race and sex in South Africa” that have largely been forgotten thanks to the propaganda that portrayed slavery as mild. The legacy of slavery continues to influence our perspectives today and is present in the prevailing attitudes towards labour provided by those who are ‘black’, evidenced in the mining, wine and domestic labour industries.

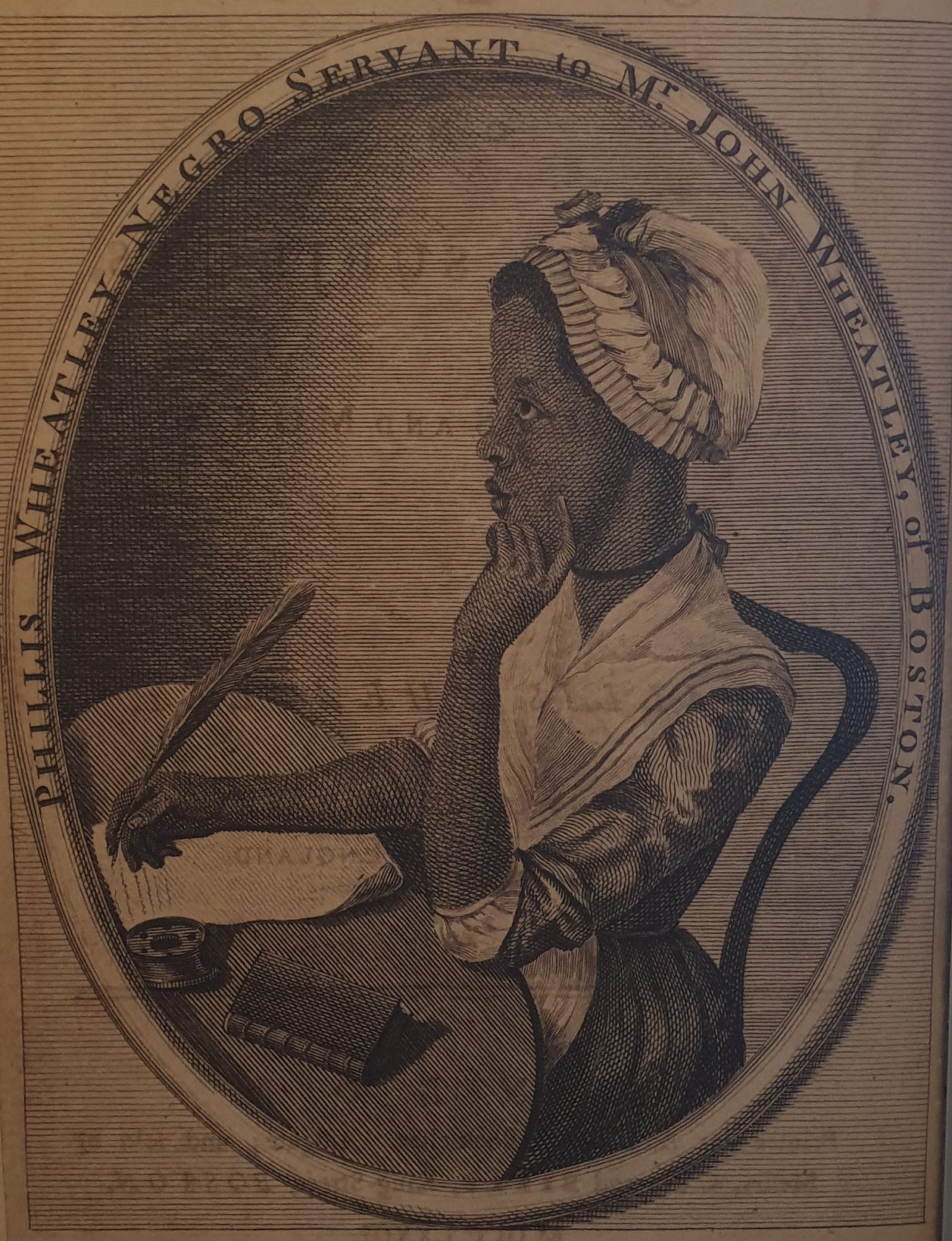

It is even present in the very names given to the enslaved. Whether from the mythological or the Biblical or after the places from which slaves came or after months of the year, these names echo the hope and tenacity of those trying to reimagine a future without chains. The months of December, January and February, for instance, hint at imagined possibilities, evident in recipes, ways of courtship, and the music we sing and dance to as we bask in the sun. In March, April and May, we see the quiet fortitude of autumn, apparent in the clothing workers of the Cape Flats who support up to nine people on their wages. In the blistery cold of June, July and August, we see what it means to achieve against immeasurable odds, of men and women raising their children and urging them to succeed; and in the quiet bloom of September, October and November, we see the promise of youth, who know where they come from, and what they and their forbearers are capable of achieving.

Note: 23 August commemorates the UN International Day of the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

Featured image: A memorial wall with the names of the enslaved who lived and worked at the Solms-Delta Wine Estate in Franschoek. The naming shows how slaves were stripped of their identity and given names that indicated where they were born, as in “Van de Kaap” or “Van Mosambique”.

This piece was published in the Cape Times, Pretoria News and The Mercury 25 August 2020 and is also online here.