Years ago I attended a women’s workshop and, as an icebreaker, we were asked to say out loud the names of the chain of strong women in our genealogies. I remember an American woman in the group who could trace her maternal line back to someone who had crossed on the Mayflower, the ship which had transported the Pilgrims from England to the New World in 1620. That was more than 300 years of history right there. It was with a vague sense of shame that I could only name my mother and her mother. I seemed lightweight, of little consequence, without any history.

I pressed my mother for more details afterwards, unable to comprehend that she hadn’t done the same to her mother. There were things you didn’t talk about, she replied to me, whispers of mixtures that were either shameful or illegal. Her mother had arrived in Cape Town, from Malmesbury, aged 14 with three younger siblings in tow, after their parents had died. They were sent to family who lived in District Six. Soon after, my grandmother went out to work at the Cavalla Cork cigarette factory to contribute to their upkeep. She hardly ever spoke about her parents, and my mother cannot recall her ever going back to Malmesbury.

As I have delved deeper into my history and that of South Africa, I have been taken on a journey that goes back hundreds of years, through apartheid, and all the way back to slavery and colonialism. Each step of the way has been a revelation, since I knew little more of our history beyond the strictly-controlled narrative presented in our apartheid-era schools. Slavery had been a subject glossed over, presented as a more benign version of slavery elsewhere, it had receded far behind the more dominant narrative of apartheid. And yet, 200 years of slavery has fundamentally shaped who we are as people and as a country.

There have been moments of depression while exploring physical, mental and psychological trauma inflicted on our people and despair over how we will ever heal and move forward as a country with such a brutal and dehumanising history. But I have also been buoyed by the spirit of resistance which brought into being a vibrant and diverse culture of music and dance, food, and language, in spite of repression.

Along the way there have been many signposts, guiding and encouraging me – Jacob Lawrence’s exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, documenting the migration of six million black southerners in the early 20th century; Isabel Wilkerson’s book, The Warmth of Other Suns, dealing with the same subject matter; the opportunity to present at a conference on Racism and Social Justice in Charleston, South Carolina, the entry point of the majority of the 12 million slaves from Africa to America, and the keynote address by Dr Lonny Bunch, the director of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History in the Mother Emmanuel Church on the second anniversary of a racially-motivated shooting.

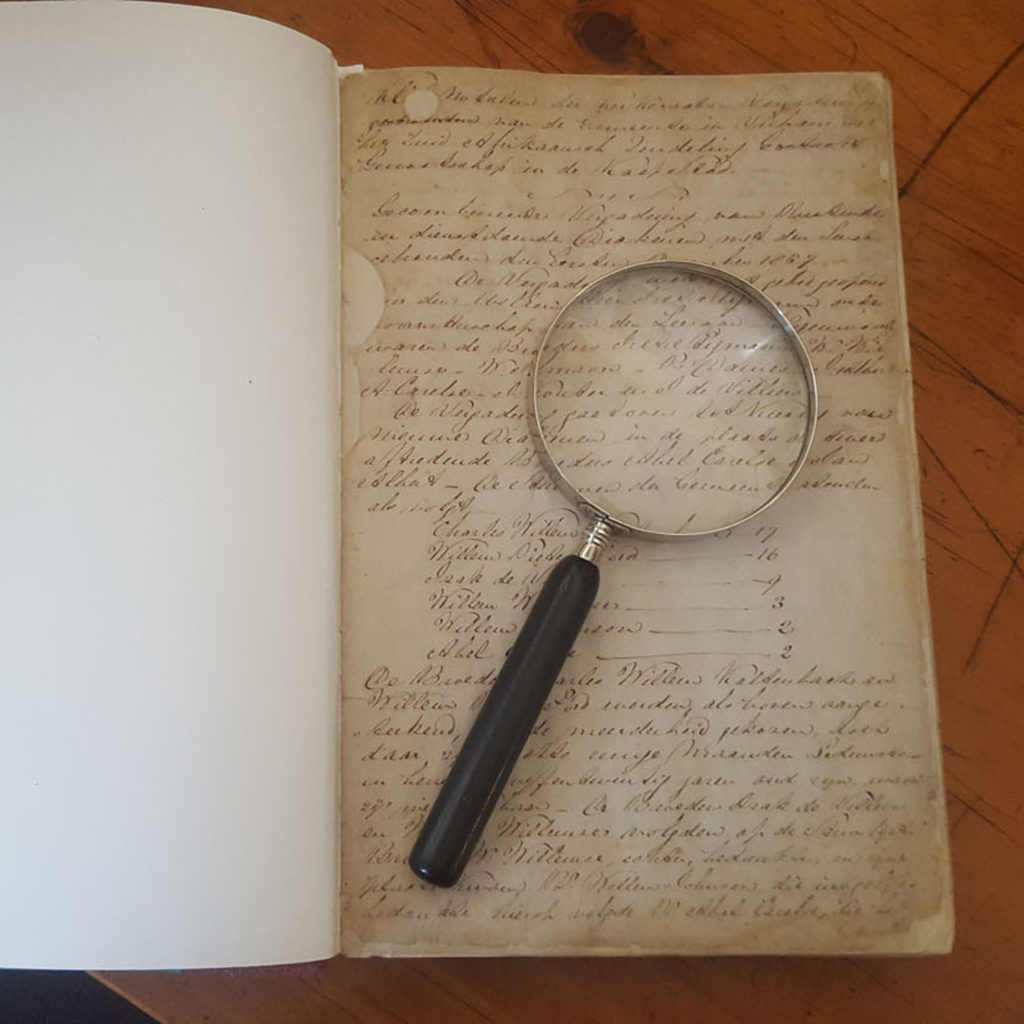

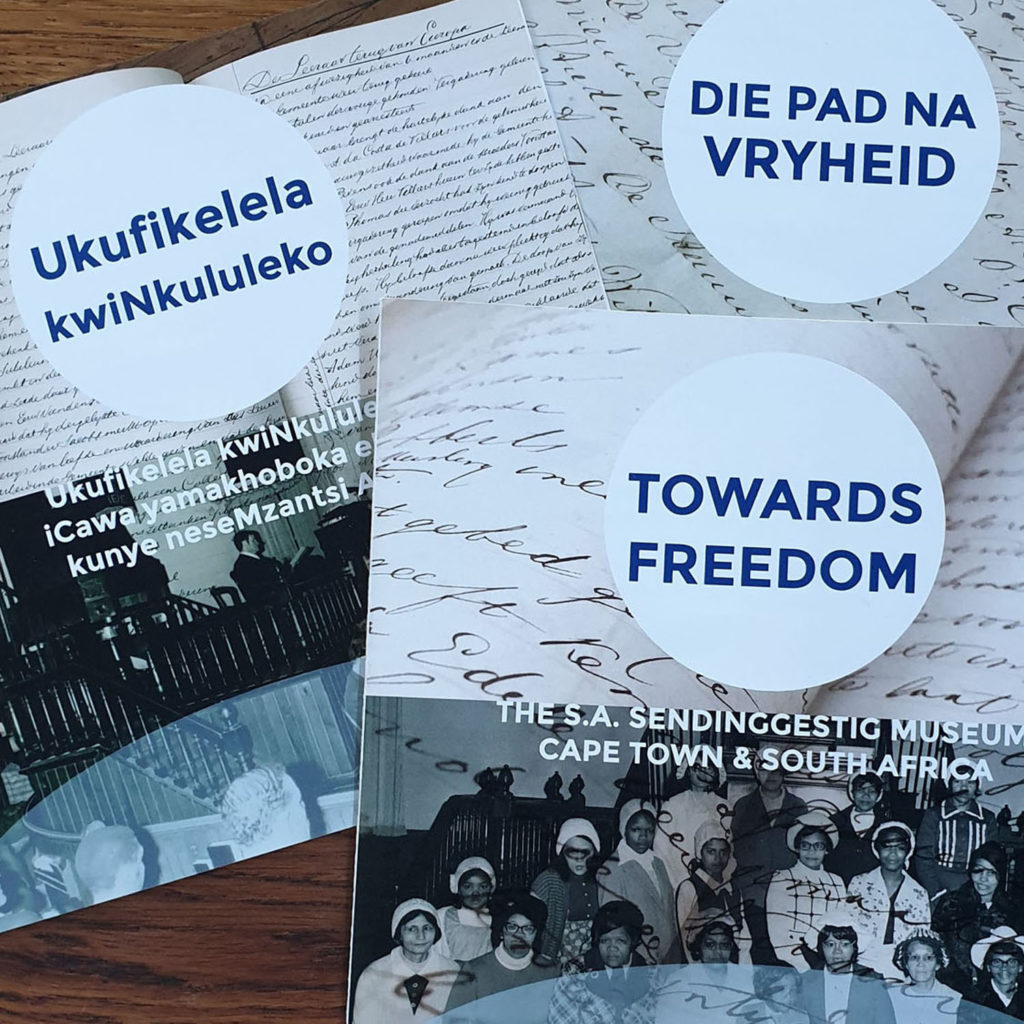

Another one of those moments occurred about a month ago when I visited the South African Sendinggestig Museum, also known as the Slave Church, in Long Street, Cape Town. It is the oldest existing mission building in South Africa and the third oldest church in the country. It’s a handsome building, with Burmese teak doors, American pine ceiling and stone from quarries on Signal Hill and Robben Island, and oak pews on which the first slaves to be baptised had sat. This led me to the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk (NGK), or Dutch Reformed Church, archives in Stellenbosch, which in turn led to an interview with Reverend David Botha, the 93 year old former curator of the Slave Church Museum. The role of the church is as fundamental to our history as slavery. A few days ago I followed that path to Genadendal, the oldest mission station in South Africa, but that’s a story for another time.

What does this have to do with my grandmother and the women’s workshop? On a wildly optimistic whim I asked Karen Minnaar, the archivist at the NGK archives, if there might be any information on my grandmother who my mother believed had belonged to the NGK in Malmesbury, before coming to Cape Town. My grandmother had switched to the Anglican Church when she married my grandfather and became a staunch supporter of the church and its women’s fellowship. I wondered if my mother was correct about the NGK. Besides, my grandmother’s surname was Adams and I had very little hope of any success with such a common surname. Hopefully, I emailed Karen her name and date of birth (the day turned out to be incorrect). Later that day, Karen emailed photographs of the baptism entry with the names of her parents and those of her godparents, along with an official document on the NGK letterhead.

I am Nadia,

daughter of Hope Lorraine,

daughter of Ethel Jeanet Silvia,

daughter of Annie.

I somehow feel validated, more solid. And proud. So was my mother when I showed her the proof of her mother’s baptism and the names of her grandparents. That’s what having a history gives you. I feel vindicated on this journey to tell our stories.

Images of my grandmother with me and my mother with me.