The Slave Church, Cape Town (2018)

The Slave Church in Long Street, Cape Town, is the oldest existing mission building in South Africa and the third oldest church in the country. The gabled cream and white façade with Corinthian pilasters, cornices and mouldings, mimics that of the Dutch East India Company’s Slave Lodge at the top of Adderley Street.

The building was probably constructed by enslaved people and free blacks for general religious activities and to prepare converts for membership of established churches. It became a separate congregation of the SA Missionary Society in 1819 and part of the Dutch Reformed Church in 1937. The church was in use until 1971 when dwindling numbers as a result of forced removals led to its closure.

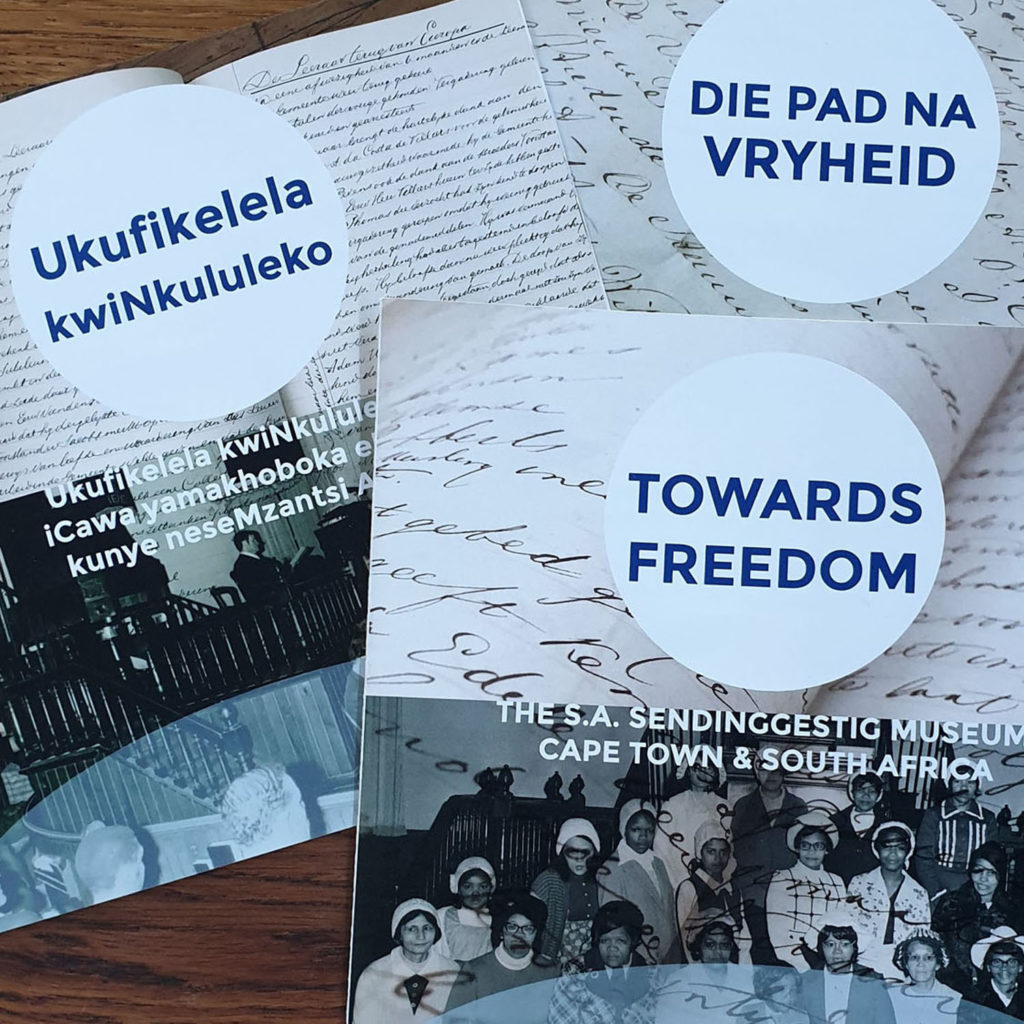

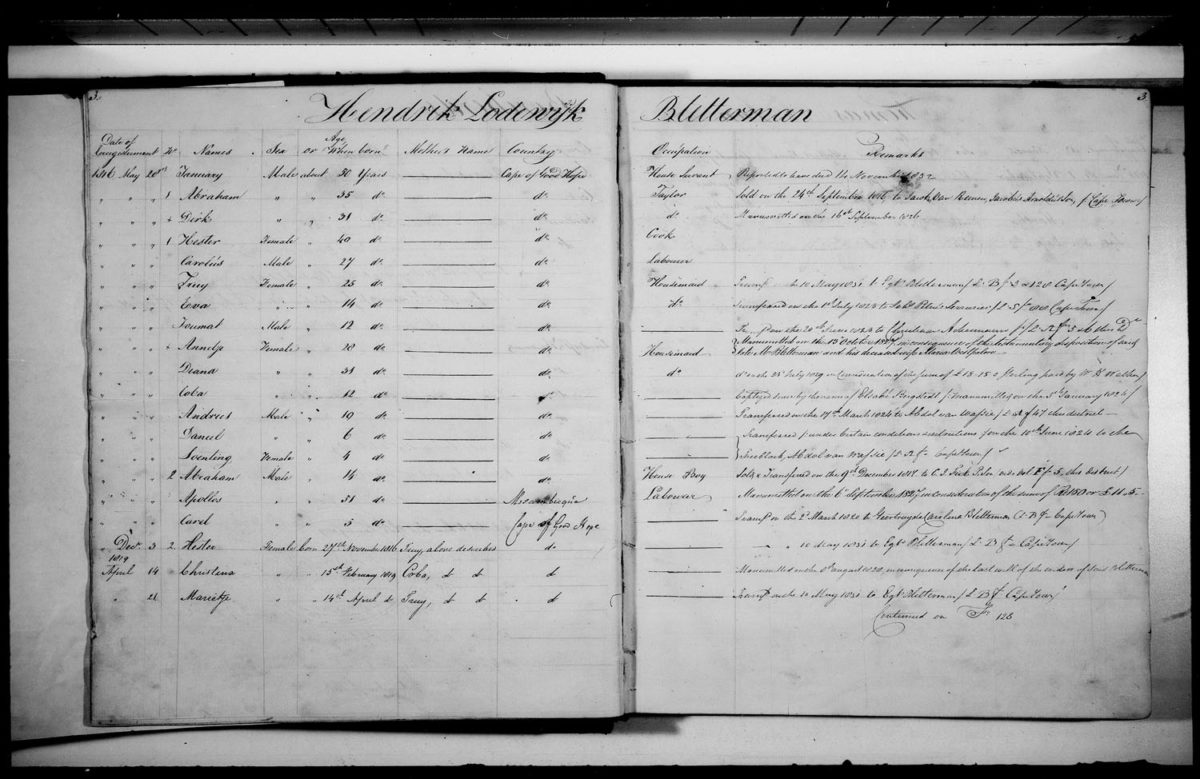

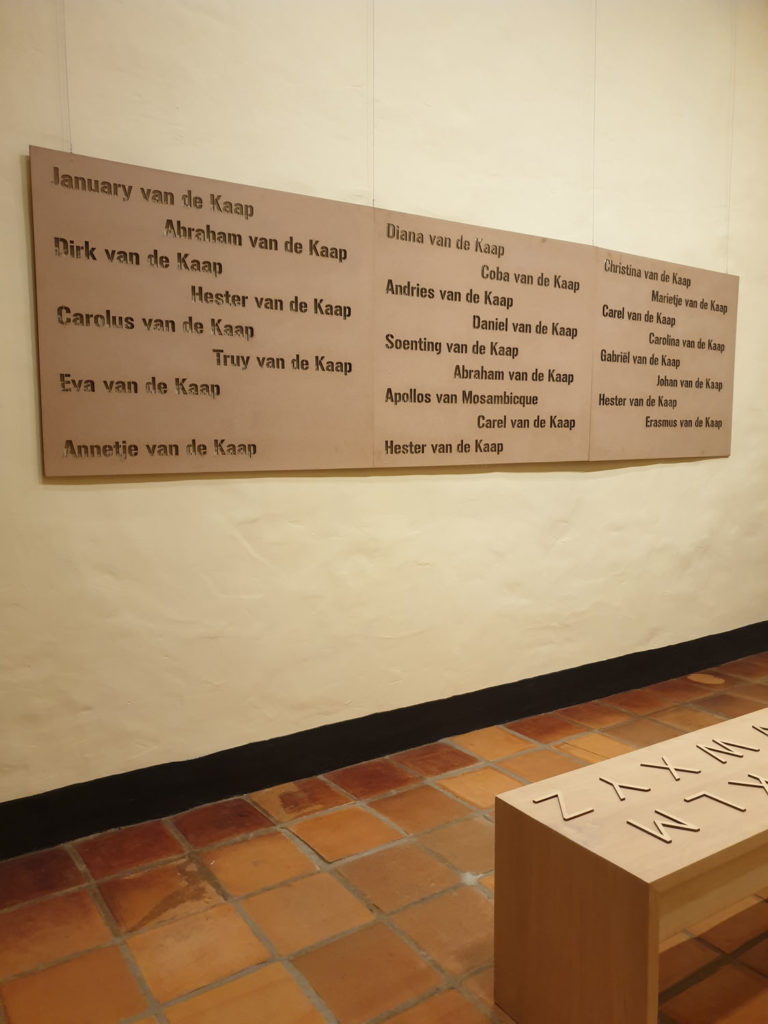

The exhibition, Towards Freedom, focuses on shedding light on the silenced histories of the people who built this building and those who worshipped here. One of the ways this has been commemorated is by printing the names of the first eight enslaved people to be baptised here, on the backs of the pews as can be seen in the photographs.

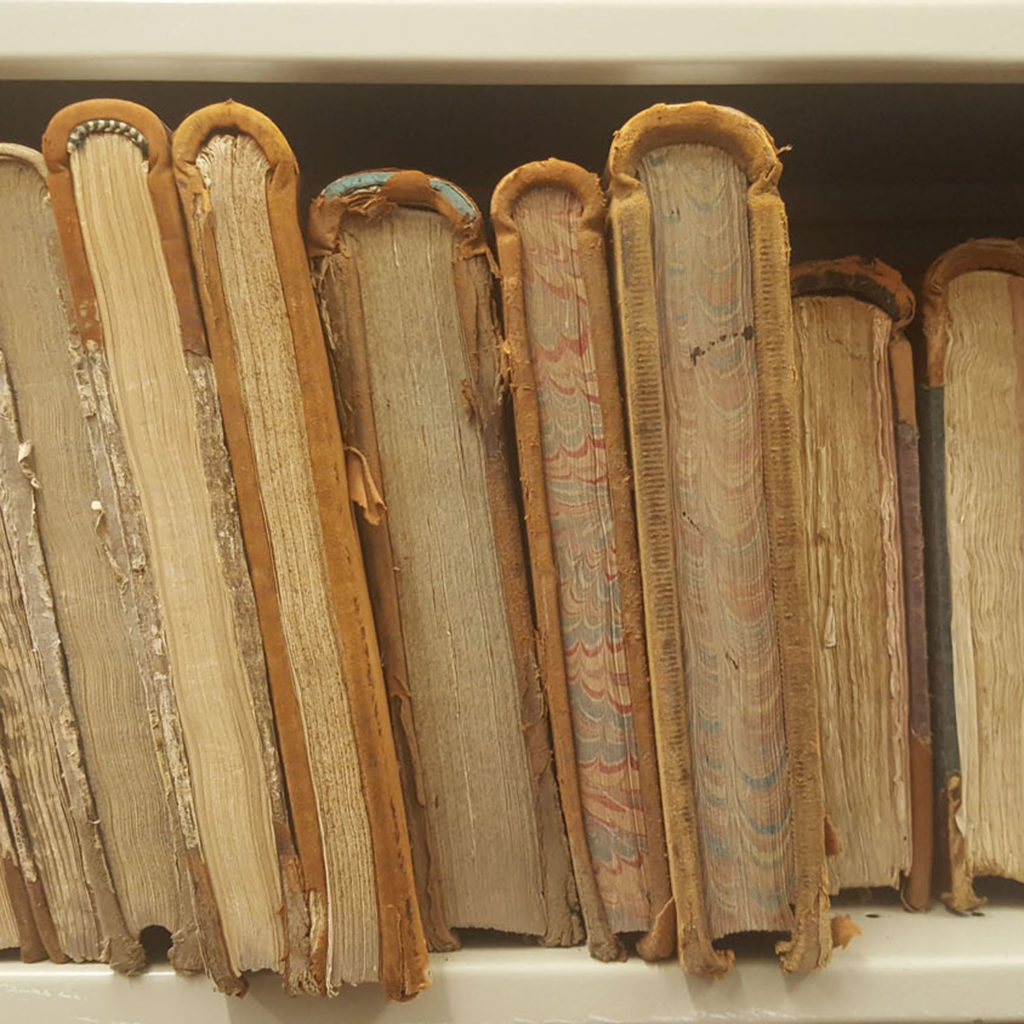

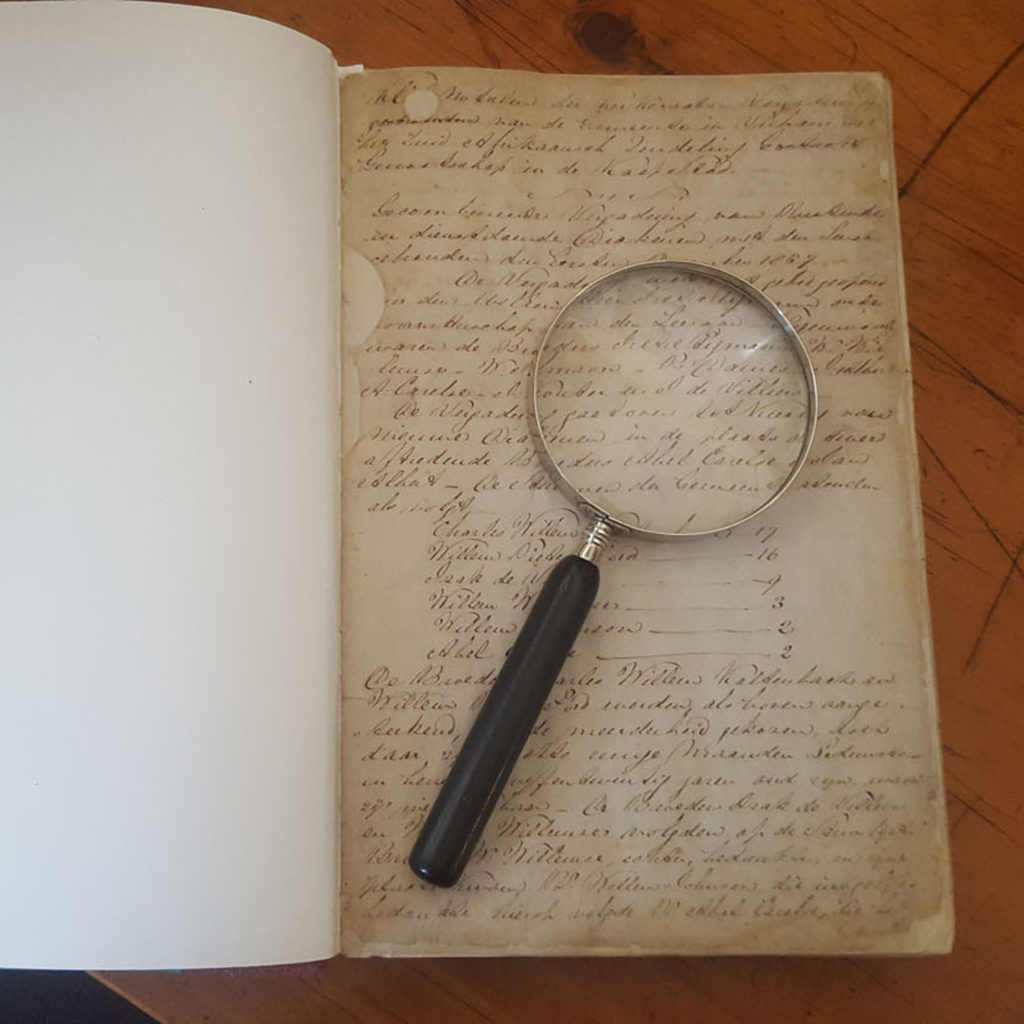

[Other images were taken at the archives of the Dutch Reformed Church in Stellenbosch, and one shows the brochures for the exhibition produced in English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa.]

Read more here: Let’s ensure slaves are more than footnotes to history

And here: Slave Church Museum