Our Cape Town Heritage (OCTH), an NPO dedicated to reclaiming “the narrative of Cape Town’s diverse culture by providing access to art through inclusivity”, invited me to collaborate on this project that grappled with the concept of colouredness within a South African context, particularly in Cape Town.

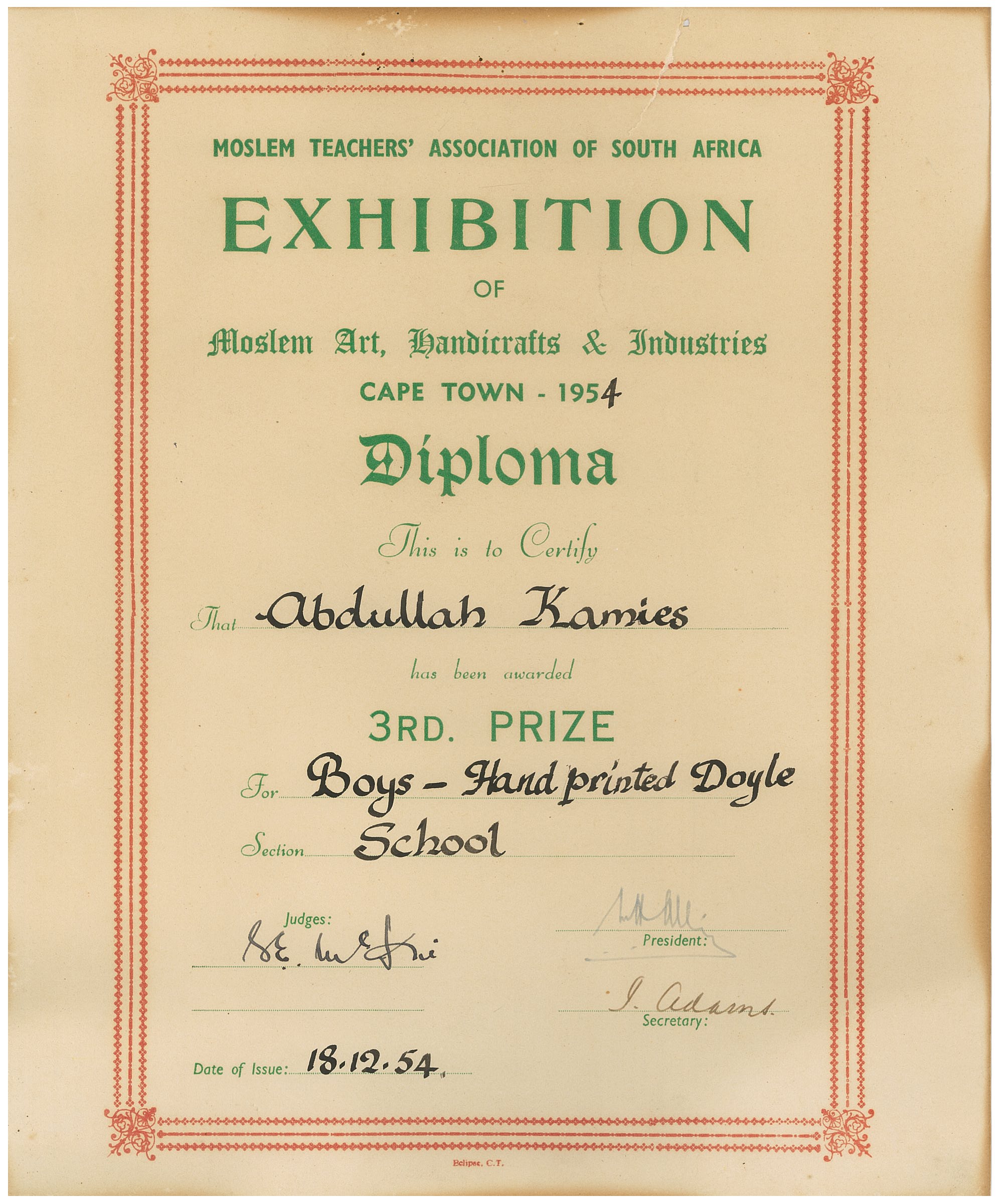

The photographs from my personal family album were showcased online in the weeks leading up to the exhibition, and were displayed as part of the physical exhibition that focused on the work of artists, Gary Frier and Kimberley Titus. Through their art they explore their own identities and cultural experiences.

In the absence of a recorded history, my family photographs have served as memory aids helping me to access the stories that bear witness to what it means to be named and understood as “coloured” in a democratic South Africa.

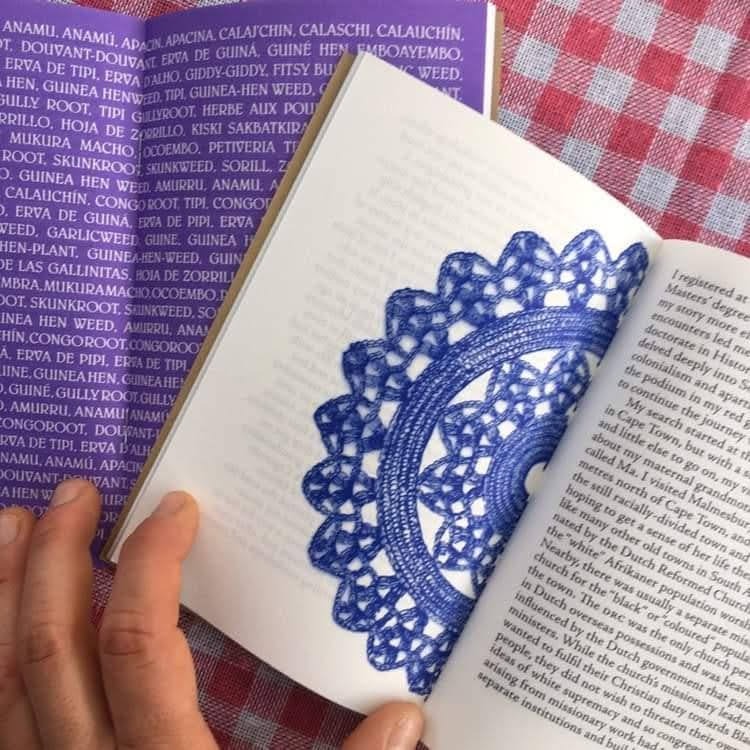

As I draw on the ordinary objects that hold cultural memory and connect us to previous generations, my grandmother’s crochet work has become a recurring theme in my writing. I have explored this creative heritage in the clay studio and the resulting ceramics were also incorporated into the exhibition.

The exhibition ran from 4-7 July 2024, and was aptly situated in the historical Bo-Kaap, on the slopes of Signal Hill. Formerly known as the Malay Quarter, this is one of the oldest residential areas in Cape Town, originally made available to free blacks and emancipated enslaved people.

Read more about the exhibition here