“In every human breast,God has implanted a principle, which we call Love of Freedom;

It is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.”

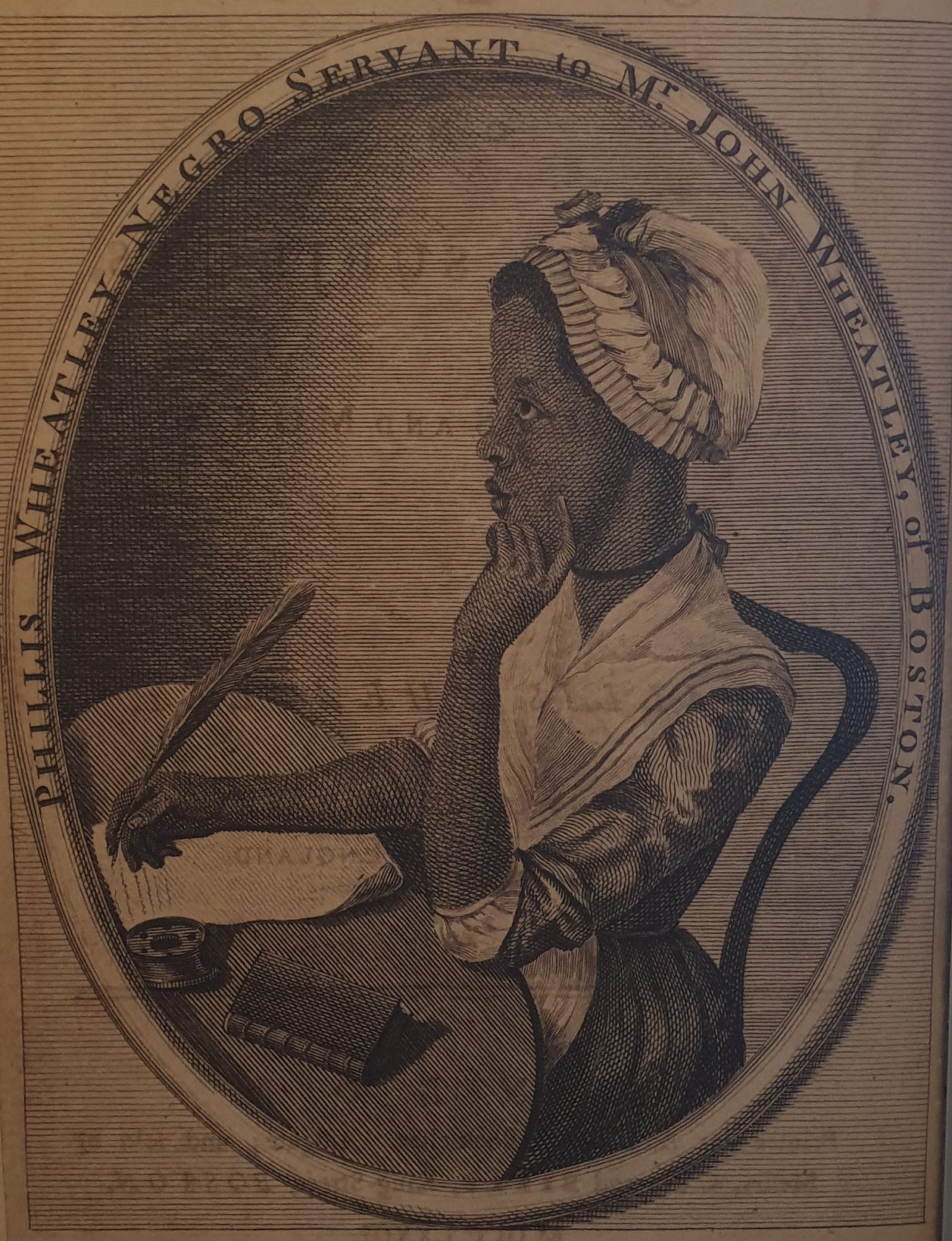

Thus, wrote Phillis Wheatley, a slave and the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry (1773). Her words could as easily have been referencing the American Revolution as it did slavery.

History is literally embedded in the streets of Boston … a red brick line runs down the centre of the pavements, through the Common and across the roads providing the guide to the Freedom Trail – revolution and resistance in every brick. The trail includes the Old South Meeting House (OSMH), a place where the Puritan congregation gathered for both secular and religious reasons, from the 17th century onward. Boston was founded in 1630 by English Puritans who fled religious persecution and the new settlement was named after the place in England from where many of them had come. The immigrants were led by John Winthrop and their goal was to build a purely Puritan society (sadly, this meant an intolerance of other religions and when the Quakers arrived in Massachusetts, they were persecuted and several were executed in the 1650s-1660s by the same Puritans).

The simple red-bricked façade of the meeting house belies the fact that one of the gatherings held here on 16 December 1773 to protest a tax, was to start a revolution. The meeting of 5 000 angry colonists resulted in what has become known as The Boston Tea Party, a protest against not only the tax on tea, but the perceived monopoly of the British East India Company. The British Parliament retaliated with a series of punitive laws, especially against the state of Massachusetts, which served only to unite the colonies and hasten the war.

Phillis Wheatley worshipped at OSMH, she was baptised there and became a full member in 1771, aged about 17. Old South’s congregation included slave-owners and slaves until 1781 when slavery was outlawed in Massachusetts. Also, in the congregation were descendants of the first Puritans, some of the town’s wealthiest families who worshiped in rented pews on the main floor and first gallery, while apprentices, slaves and servants sat on free benches in the top gallery.

Born in Gambia, West Africa, Wheatley was sold into slavery at the age of 7 or 8 and transported to North America where she was sold to the family, who gave her her last name. Her first name was derived from the name of the ship that brought her to America. In one of her poems she ponders plaintively,

… what pangs excruciating must molest; what sorrows labour in my parents’ breast!

Those few words capturing the pain and hurt inflicted by slavery, not only on the enslaved but on the family they left behind. Wheatley’s book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was signed by John Hancock and other Boston notables – 17 men asserted that she had indeed written it. She was emancipated shortly afterwards.

In about a week, I embark on a tour of the South with four graduate students from the University of Pretoria. Our journey, which we have dubbed UP Freedom Riders’ Trip, will start in New Orleans and then we meet up with a contingent from Indiana University. The following week is hectic – Memphis, Jackson, Selma, Montgomery, Birmingham and Atlanta, ending in Washington, DC from where the students will fly back home.

My few days in Boston are personal and not officially part of this trip but the experience has made me consider how waves of immigrants have come to America, often forced by circumstances beyond their control and how they have been persecuted by those who preceded them, often in much worse scenarios.

In 1829, another Bostonian, African American writer and abolitionist, David Walker, published a pamphlet entitled Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America. In it, Walker argued for the immediate abolition of slavery rather than the gradual phasing out of the institution and also for the right of every African American to become a full and equal citizen of the United States, rather than the return of freed slaves to America. His ideas would influence the abolition movement long after his death a year later. But it is his poignant question which continues to echo in my head.

Was your suffering under Great Britain one hundredth part as cruel and tyrannical as you have rendered ours under you?

*The Golden Rule – the principle of treating others as you would like to be treated; it is common to many religions and cultures.

Photograph of Wheatley etching taken at the exhibition at the Old South Meeting House in Boston